Designing the Gate: Inside Australia's Cyber Professionalization Effort

11 Nov 2025After months of digging - investigations, confidential conversations, FOI requests - I can finally lay out a comprehensive, end-to-end, documented account of how cybersecurity professionalization emerged in Australia.

The story starts in 2020, when the Department of Home Affairs released Australia’s national Cyber Security Strategy (1). Buried in it is Objective 70, which states:

“Businesses and the community need to have confidence in the cyber security industry. The Australian Government will continue to work with businesses on the best way to promote the cyber security profession and ensure there are clear professional standards for practitioners, and more consistency in the market for consumers. In the medium to longer term, this could involve exploring whether there is a need for cyber security accreditation frameworks, including how these would map against other existing licensing and professional accreditation frameworks. To provide consistency across the cyber security sector, this could be accompanied by professional competency requirements for maintaining accreditation.”

To be accurate, the idea of professionalization and occupational licensing wasn’t new in 2020. Industry conversations around it date back at least to 2016 (2) - likely earlier. So it was not unreasonable for Home Affairs to examine whether Australia needed a licensing or accreditation scheme for cybersecurity professionals.

With the objective now part of the national strategy, industry peak bodies and proponents of professionalization began providing advice to government on how a potential scheme could be designed and implemented. (2, 7, 20)

And since the Australian Information Security Association (AISA) is the largest and most influential industry body, the first chapter of this investigation begins with how early conversations took shape inside its board.

The Clash Inside Australia’s Largest Cyber Association

In 2022, inside the board of AISA, an internal debate unfolded.

One board member strongly advocated for AISA to lead the professionalization of the cybersecurity industry. In August, he began drafting what would become multiple versions of a proposed professionalization framework. (3)

A key concern raised during the discussions was whether such a scheme might advantage certain certification providers over others, while also increasing the cost for cybersecurity professionals to practice.

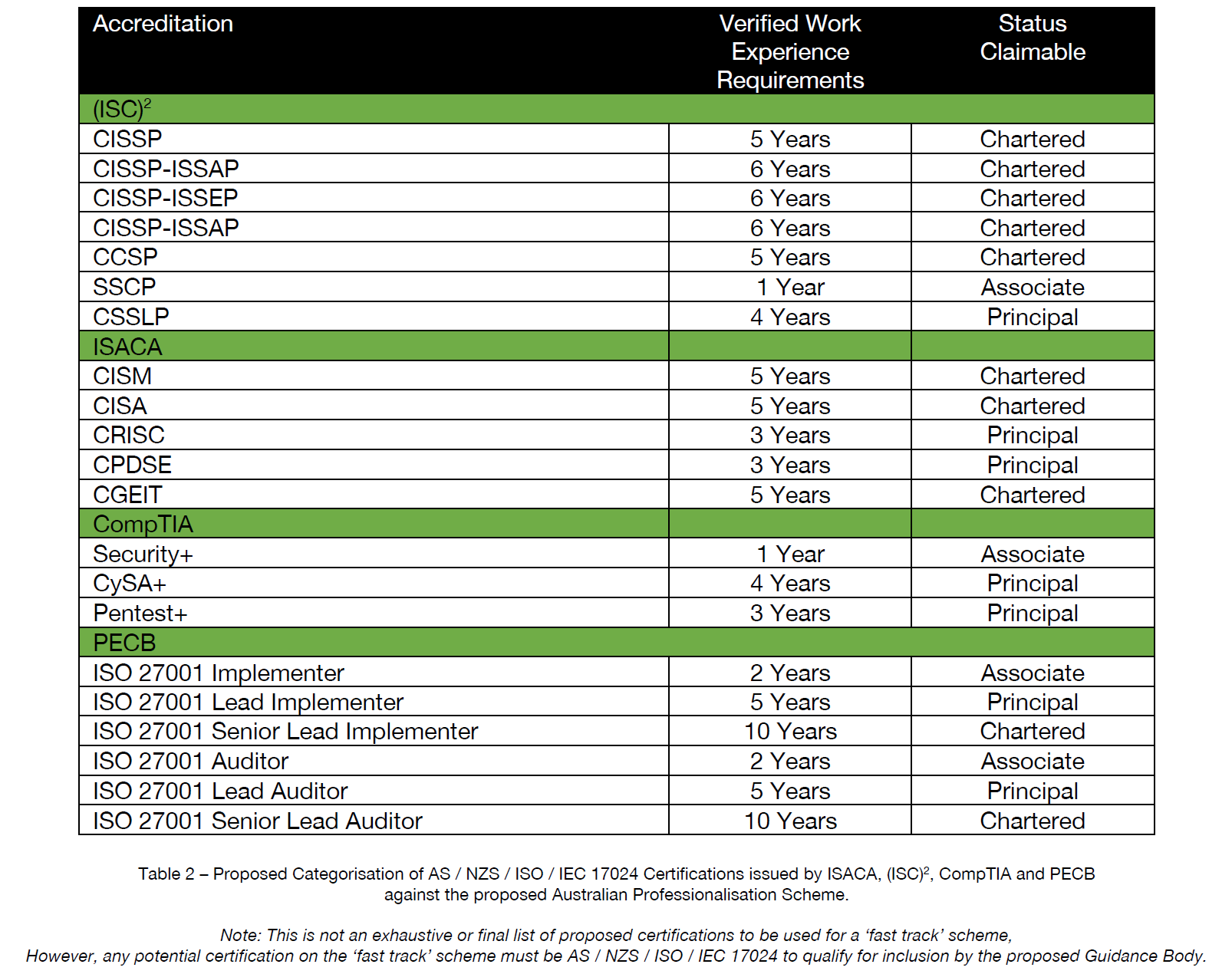

Notably, the board member had previously served for four years as the Director of Cyber Security Advocacy for ISC2. In his proposal, ISC2 - alongside ISACA, CompTIA, and PECB - was positioned as a “fast-track” pathway to accreditation: (3)

Ultimately, these discussions led AISA to survey 9,500 members in September to gauge support for professionalization (4) - the second time AISA had canvassed member views on the issue, following an earlier survey in 2019.

At the centre of the debate was one key finding:

“Slightly more than half (53.1%) of AISA’s members want to see regulation and accreditation of the sector to ensure a base level of qualification and standard. It is notable that although only about a quarter (26.4%) of respondents do not want a certification scheme and the remainder (20.5%) are ‘unsure’.”

Shortly followed by:

“If forced to make a binary decision, a study conducted by AISA in 2019 found almost one in three cyber security professionals do not support accreditation.”

To the best of my knowledge, AISA’s two surveys remain the only dataset capturing industry sentiment on professionalization.

Supporters of professionalization highlight that 53.1% of respondents expressed a desire for regulation and accreditation. Those opposed — or unsure — point to the other findings, including:

- Industry leaders not supportive of accreditation

- Industry certification is not consistent in the sector and currently disadvantages women

- Support was highest in academia: 73.8% in favour, 14.8% opposed

Ultimately, AISA chose not to pursue professionalization at that time. With that decision, the push for a national scheme shifted from AISA to AustCyber.

The Hidden Conversations inside AustCyber That Influenced National Policy

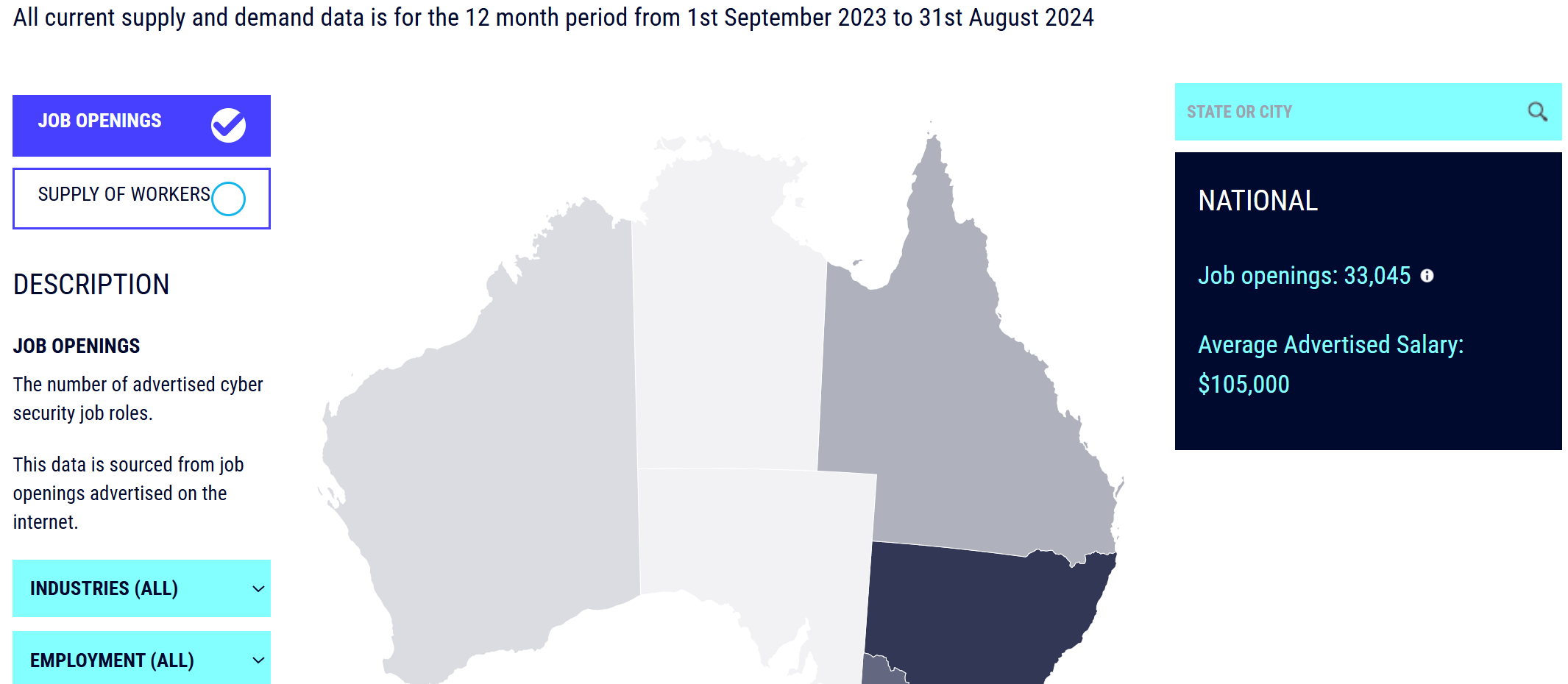

In 2021, AustCyber received $291,500 to develop a tool to analyze and forecast the growth of Australia’s cybersecurity workforce (5, 6).

The project resulted in a website called AUCyberExplorer.

This project produced data that later became central to arguments for a professionalization scheme. For instance, one document cited figures showing the cybersecurity workforce numbered 51,309 people, with 7,070 job openings advertised. (7)

In another example, the project produced interactive maps highlighting current demand for cybersecurity roles and projecting future workforce needs:

In February 2021, AustCyber underwent a major change — it was acquired by the private company Stone & Chalk. (8)

Several key details are worth noting. The former AustCyber CEO officially announced her departure in March 2022. (9)

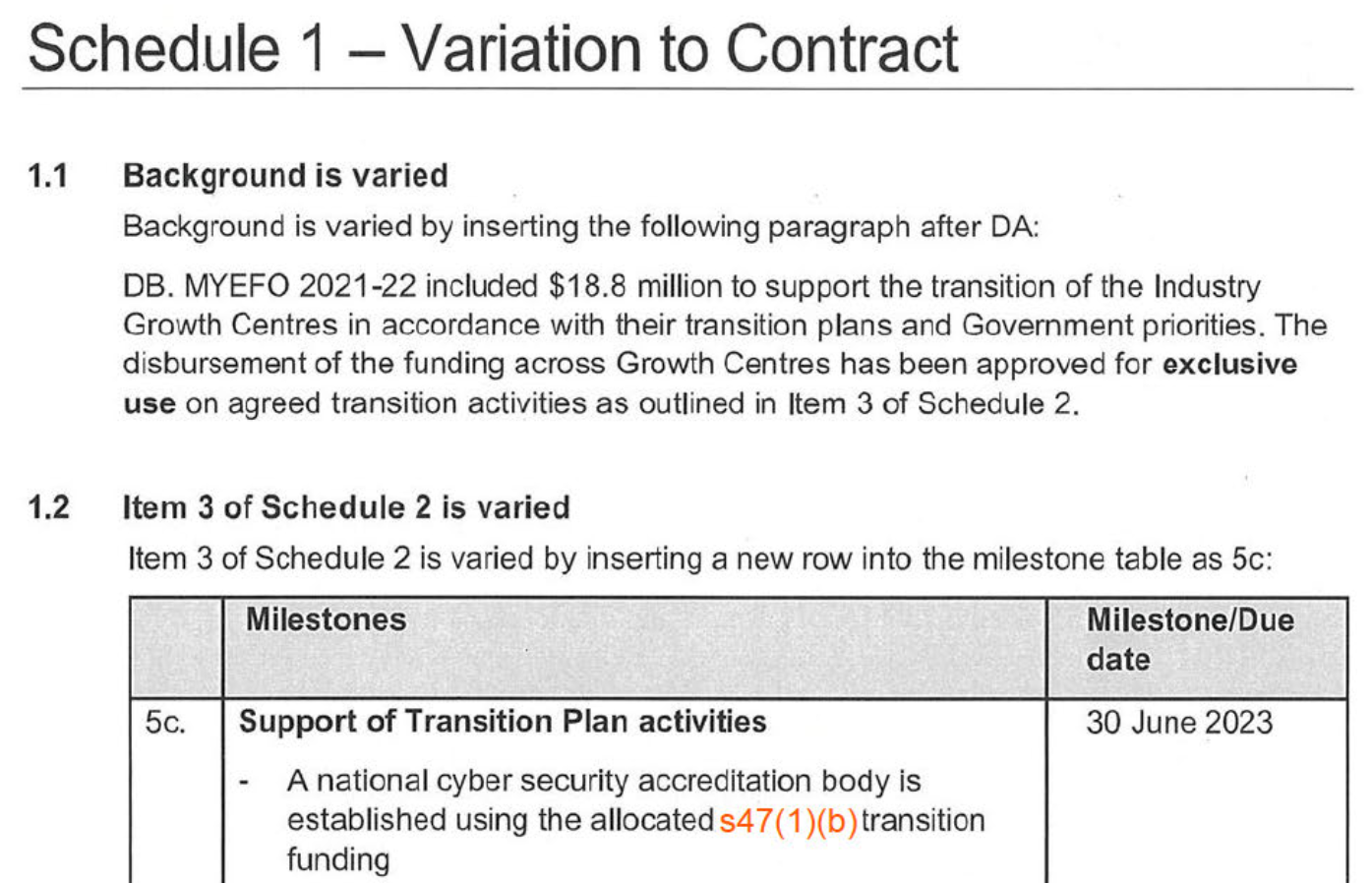

In April 2022, under its Transition Agreement with the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR), AustCyber signed a Deed of Variation committing to design a national cybersecurity accreditation body by June 2023: (7)

In September 2022, a new Group Executive had been appointed (10) and part of his role included the delivery of this project for DISR.

Who first conceived the initiative remains unclear. To this day, no public documentation explains why AustCyber took on this project or identifies the individuals behind it.

Once the contract was signed, the wheels were set in motion. AustCyber established a group called the Australian Cyber Security Professionalisation (ACSP) Program.

The ACSP consisted of ten founding members, each bound by a strict non-disclosure agreement with AustCyber: (7, 11, 12)

- AustCyber

- ISACA

- ISC2

- RMIT University

- TAFE Cyber

- Tech Council of Australia

- The Australian Computer Society (ACS)

- The Australian Information Industry Association (AIIA)

- The Australian Information Security Association (AISA)

- An individual who had been the Director of Cyber Security Advocacy for ISC2

Together, they began designing and implementing an accreditation framework structured around a three-phase plan: (7)

They described their approach as a “co-design” process.

In principle, co-design is a collaborative process that emphasizes designing solutions to problems with people who are affected, rather than for them. (13)

Therefore, the ACSP committed to collaborate with multiple partners.

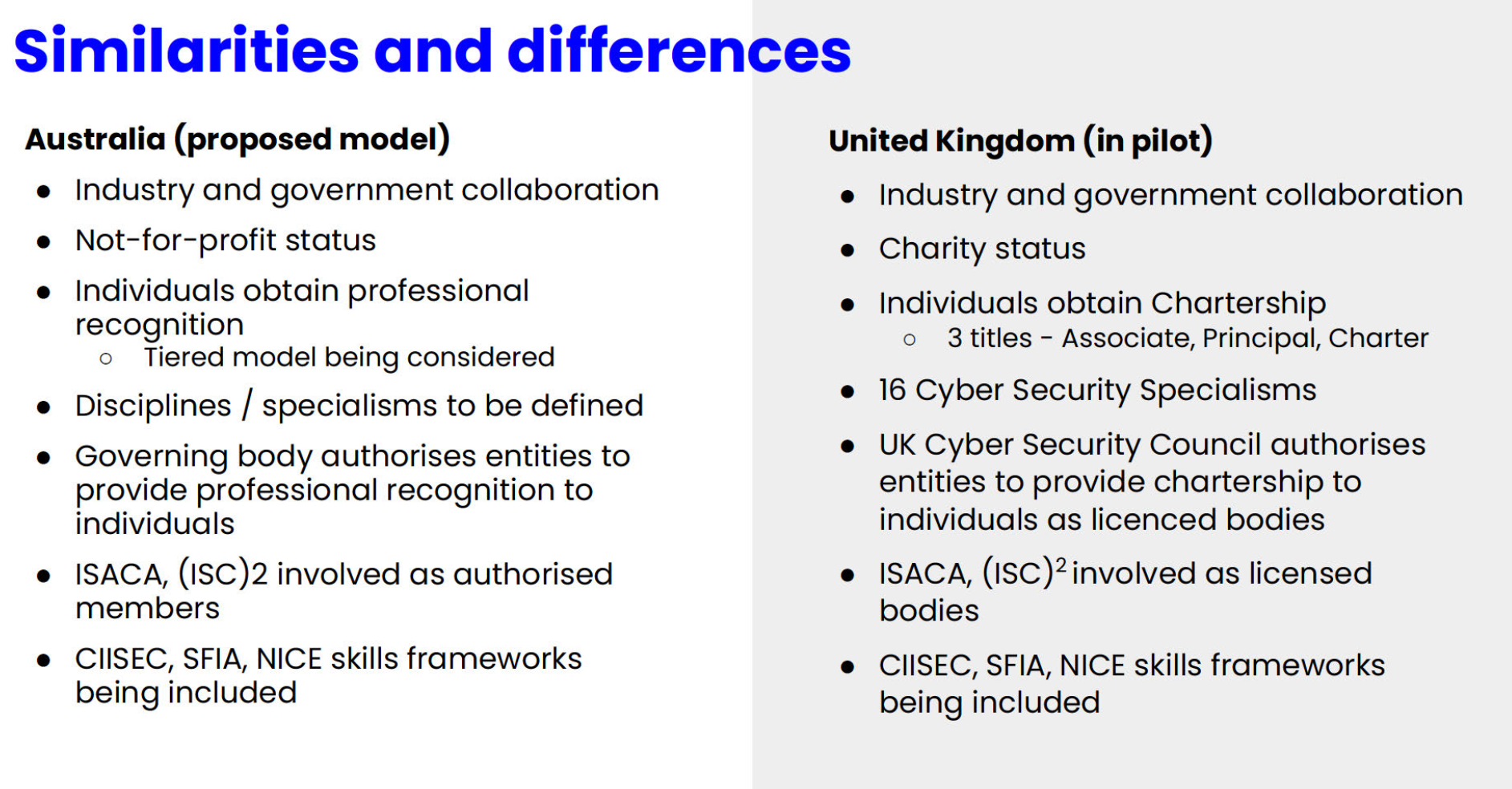

Government partners included the ACSC, Home Affairs, APSC, Jobs and Skills Australia, and DEWR. Industry collaborators ranged from Engineers Australia and the Digital Skills Organisation to the UK Cyber Security Council.

The ACSP also engaged with private organizations involved in training and recruitment. Notably, it met with Fifth Domain, which in 2022 received a $3.3 million grant from DISR to expand the cybersecurity workforce by at least 100 people by 2024. (7, 14, 15)

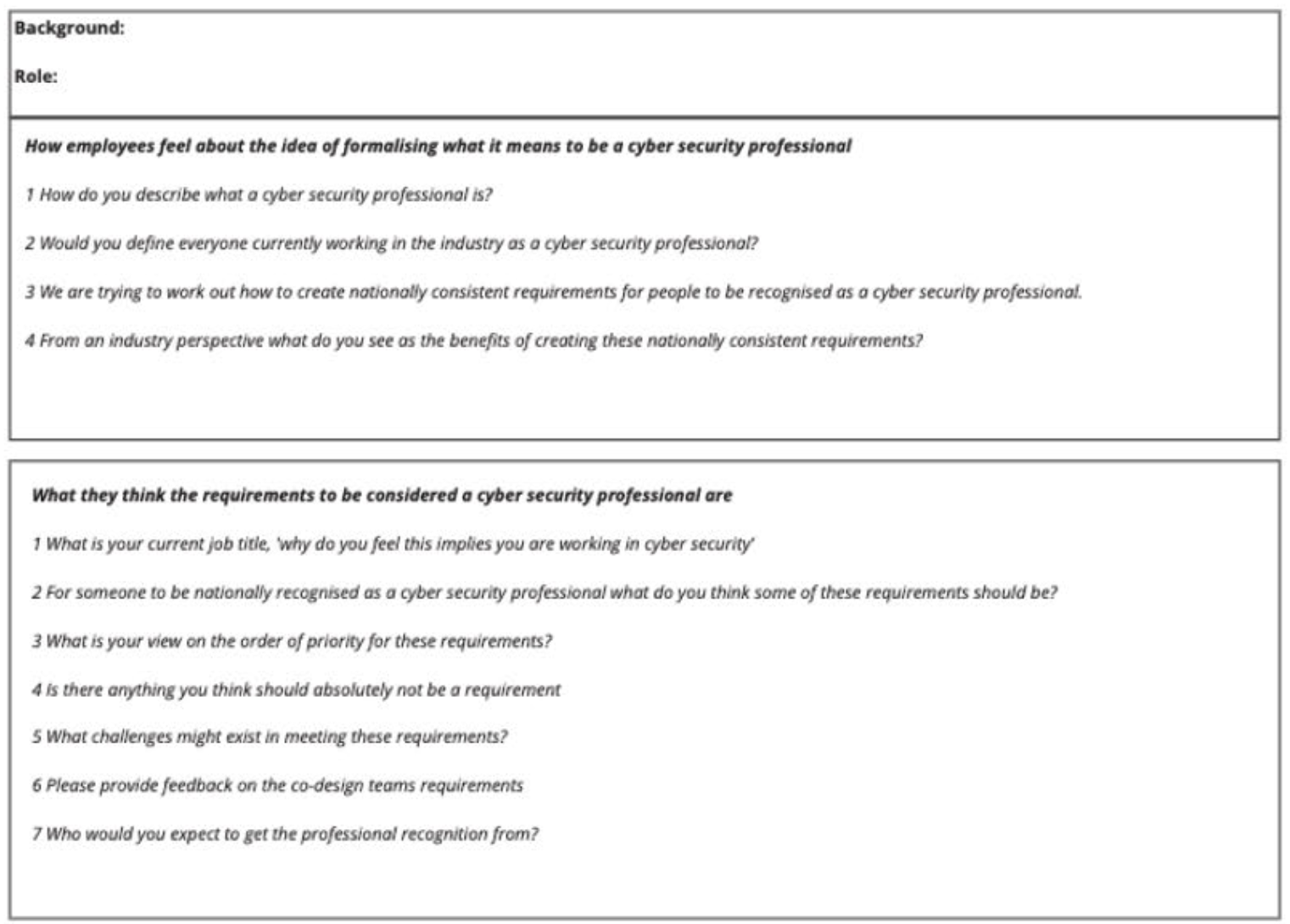

The ACSP carried out one-hour, one-on-one interviews with 25 employees and 20 employers. The FOI documents provide no information about who these individuals were or on what basis they were deemed representative of the industry.

The image below provides a sample of the questions they used:

In the end, the ACSP reported strong support for professionalization and proposed the following model:

The Moment AISA Drew the Line

While AISA was a member of the ACSP, it became increasingly uneasy with the direction of the work and the public announcements being made. (2)

Some board members remained concerned that the proposed professionalization model could advantage certain training providers while unnecessarily increasing costs for cybersecurity professionals. (2)

It’s important to note that AISA was not categorically opposed to professionalization itself - several board members supported the idea in principle. However, due to these concerns, AISA ultimately chose to withdraw from the ACSP. (16)

Over the following months, AISA began publicly articulating its position on professionalization.

For example, it independently provided the following advice to the Department of Home Affairs: (17)

“Although some organisations have struggled to find individuals with the necessary skills to fill vacancies, the issue facing the sector is more multifaceted than merely implementing professionalisation, accreditations or investing in additional industry-based training programs.”

And a few pages later:

“Support for professionalisation of the sector continues to be mixed with the biggest proponents of professionalisation in the academic sector. […] It also raises the question, what problem is professionalisation trying to solve, especially if it is not supported widely by industry?”

And:

“Workforce issues relating to skill shortages in the supply and demand side are complex and cannot be resolved by using professionalisation or accreditation. It should be noted that professionalisation or accreditation will only disadvantage more women and drive them away from the sector”

The Persistent Peak Bodies Behind Professionalization

Ultimately, DISR did not awarded the national professionalization mandate to the ACSP. The reasons for this remain unknown. However, the outcome produced an interesting dynamic: while some of the participating organizations continued to promote professionalization in a coordinated way, they also began competing with one another for the opportunity to lead its implementation.

For instance, during the 2023–2030 Cyber Security Strategy consultation process in February 2023, I searched all 220 public submissions received by Home Affairs and found that only six explicitly recommended professionalization. (20)

Of those six, four came from organizations involved in the ACSP (AustCyber, ACS, AIIA, Engineers Australia) and one from the individual who had led it. (20)

Ultimately, the effort paid off. In November, Home Affairs released the Cyber Security Strategy 2023-2030, which included professionalization as a key outcome the government committed to deliver. (21)

A year later, in December 2024, Home Affairs announced a $1.9 million grant opportunity for a consortium to design, promote, and pilot a professionalization scheme for Australia’s cybersecurity workforce. (22)

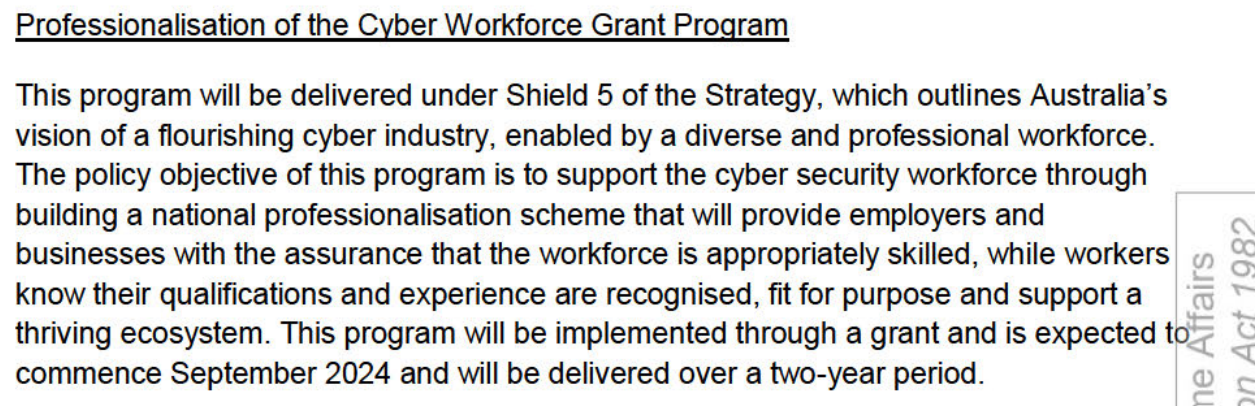

A member of the cybersecurity community submitted a FOI request to Home Affairs seeking the rationale and objectives behind the grant. (23)

The image below shows what was uncovered:

Although the FOI release is heavily redacted, the portions that remain visible suggest the government views professionalization as an appropriate market intervention to achieve the following outcomes: (23)

- Provide quality assurance for employers

- Reduce barriers to entry into the cyber industry

- Attract and retain diverse talent, and foster inclusive cultures

- Enhance domestic cyber capabilities

- Increase industry and business confidence in Australia’s cyber security workforce

The grant opportunity document does not mention the ACSP or AustCyber. It was issued by Home Affairs, while the ACSP was funded by DISR - two separate departments. Yet both make the same conjecture: that professionalization is a necessary market intervention that can achieve the goals outlined above.

The Moment the Industry Drew the Line

In January 2024, the wider industry began to take notice. The grant documents suggested that Home Affairs was responding to “industry calls” for professionalization (23), yet many were unclear about who had made those calls or what had been said.

This sparked a wave of discussion across social media, which I encouraged, as I suspected that Home Affairs had not been made aware of the concerns many in the industry hold about professionalization.

I went on to gather points of view from 40 senior leaders and organized their feedback into seven recurring themes: (24)

- There is mixed support for a professionalization scheme

- Many are concerned that vested interests will hijack the scheme

- The scheme oversimplifies a deeply complex profession

- There’s a misalignment between the scheme’s goals and proposed solutions

- The scheme’s return-on-investment (ROI) lacks evidence

- Malicious actors will game the system without mastering the skills

- The scheme ignores the broader context within which professionals operate

A pivotal moment in the industry’s response came with the publication of a peer-reviewed scientific paper by Michael Collins, which applied Systems Thinking and a literature review to assess whether any evidence supports the claim that professionalization achieves the objectives outlined in the grant. (18)

Using a scientific approach, Collins found that professionalization is strongly correlated with outcomes that contradict those goals:

- It reduces industry size by raising barriers to entry.

- It increases practitioner earnings and service costs.

- It only improves service quality when standards are set extremely high - a condition that further shrinks the workforce and raises costs.

Collins’ findings align with broader academic and scientific research on professionalization, including the work of legal scholar Rebecca Allensworth and other professors, scholars and scientists. (19)

ACS Wins The Pilot

The Australian Computer Society (ACS) submitted a proposal to the grant that proposed to form a consortium with AISA, AWSN and Aus3C.

After the stir I caused over the phrasing of AISA’s newsletter announcing their partnership (25), they graciously invited me to a friendly debate at CyberCon Canberra 2025:

That’s when I learned more about their proposal - one I haven’t seen directly, but understand to be industry-led, co-designed, and centred on developing a skills framework aligned with SFIA.

As of 7 November 2025, no formal announcement has been made regarding the grant’s recipient. However, the ACS has posted an open position for a Project Coordinator to lead the delivery of a program focused on professionalizing the cybersecurity industry:

Several confidential sources have since informed me that the ACS has been awarded the grant.

The ACS, previously involved in the ACSP, now appears positioned to lead the professionalization pilot.

Limitation

This account is based on documents obtained through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests and publicly available sources. It cannot capture private communications or deliberations that may provide additional context.

Final Words

This section is my honest opinion.

Those against or uncertain about professionalization have scientific evidence on their side showing that studies in other sectors associate it with smaller labour pools, higher costs, and delivers little to no measurable improvement in service quality. (18)

There also is evidence that professionalization boards can act like cartels - a group of competitors who conspire to insulate themselves from competition. (19)

Those in favour lean on values-based arguments that frame professionalization as essential for protecting quality and safety, preventing charlatans, and curbing incompetence.

Supporters argue that a structured professional framework could increase employer confidence, align education pathways, and improve public trust in cybersecurity professionals - particularly in sectors handling critical infrastructure. These are legitimate policy aims, even if the empirical basis and cost–benefit trade-offs supporting them remain contested.

Debates on professionalization often stall because proponents prioritize normative reasoning (what should be) over empirical evaluation (what is).

My goal in writing this comprehensive account of professionalization in Australia is to move supporters into the unsure camp.

I want proponents to see that strong evidence and credible arguments reveal serious flaws and risks that must be addressed before the professionalization scheme is implemented - even under a pilot.

If you agree with the historical account and evidence presented here, I invite you to join me in advocating for science-based methods, evidence over ideology, error correction, and true transparency and accountability — to ensure the accreditation scheme is governed in the industry’s best interest.

What Wasn’t Done by the ACSP - and Why It Matters

The following findings summarise key activities and governance practices that do not appear in any of the documents produced by the ACSP, as obtained through FOI requests:

1) Stakeholder Representation and Consultation Gaps:

1.1. The ACSP conducted interviews with only 25 employees and 20 employers. (7)

1.2. This sample size is too small to represent the broader cybersecurity ecosystem.

1.3. For a professionalization scheme to gain legitimate adoption, a significantly larger and more diverse group of affected stakeholders must be consulted and have their feedback integrated into the scheme.

2) Absence of Scientific Validation:

2.1. The ACSP described its approach as co-design, but did not demonstrate the use of recognized scientific validation methods. (7)

2.2. None of the available documents reference or cite peer-reviewed research. (7)

2.3. The absence of a scientific foundation raises questions about the validity and reliability of the ACSP’s conclusions and its proposed model.

2.4. A credible professionalization model should be grounded in established scientific methods and supported by independently verifiable evidence.

3) No Formal Risk Assessment and Impact Analysis:

3.1. The ACSP documents show no evidence of a formal risk assessment and impact analysis being conducted or reported to government. (7)

3.2. Professionalization raises barriers to entry for new professionals and can reduce the overall workforce size (18).

3.3. It can also increase costs for employers and service providers, affecting market competitiveness (18, 19).

3.4. Without risk analysis or mitigation planning, these economic and structural consequences remain unexamined and unmanaged, increasing the risk of unintended labour-market distortion.

3.5. A responsible design process should identify, assess, and address such risks before implementation.

4) No Management of Conflicts of Interests:

4.1. ISC2 and ISACA were core members of the ACSP. Both sell cybersecurity certifications and therefore stood to gain financially from being designated as “authorized members” by the professionalization peak body.

4.2. Other participating organizations - including ACS, AIIA, AISA, and AustCyber - could likewise benefit from a fee-based accreditation model involving annual memberships, registrations, and renewals.

4.3. Given these potential financial interests, the ACSP should have established a formal conflict-of-interest management process to preserve impartiality.

4.4. The absence of such a process compromises the perceived neutrality of the ACSP’s findings and the credibility of the model it proposed.

5) Diagnosing Symptoms and Not Understanding Systems:

5.1. The ACSP identified several potential issues in the cybersecurity industry - such as the proliferation of certifications, inconsistent course quality, and fragmented roles.

5.2. However, it did not conduct a whole-system analysis to examine the underlying parts, structures, relationships, and mental models shaping education, certification, recruitment, and employment.

5.3. Nor did it perform a webs-of-causality analysis to distinguish between problems a professionalization scheme could address and those it could not. Instead, it focused only on examples supporting the need for such a scheme and did not test disconfirming hypotheses.

5.5. Without this deeper analysis, the proposed model is likely to contain contradictions, overlook key factors, not match up to reality, and fall short of its intended outcomes.

ACSP Right of Response

On the 11th of November 2024, I contacted the Group Executive who led AustCyber during the time of the ACSP and two of its members to request answers to the following questions:

1. Which party initiated the ACSP: AustCyber or DISR? Who was the executive that negotiated for a national cybersecurity accreditation body to be included in the Transition Agreement?

2. How was it determined that the 25 employees and 20 employers were representative of the entire industry?

3. Was a risk assessment and/or economic impact analysis ever performed? If so, please provide the evidence.

4. How were risks of conflicts of interest managed? Provide evidence.

5. Which scientific methods were used to validate the findings documented in the ACSP’s report(s)?

6. Do you have any comments you would like me to consider before I publish an article on this FOI?

The Group Executive explained that he had not been directly involved in the ACSP process and had inherited it upon taking up his role at AustCyber. He added that he supports a process that is “transparent, consultative and focused on public benefit, not one driven by personal grievances, commercial conflicts and/or revisionist narratives.”

One ACSP member stated that he had signed a strict NDA with AustCyber and was not permitted to comment. He also clarified that he played no part in the Transition Agreement. He also said that he had “queried the methodology used to compile that [AISA] survey on the board [he] was told by the chair at the time that owing to conflicts I was not entitled to know the methodology.”

Finally, he said that although he had been part of the ACSP, he had not seen all of the documents released through the FOI request, and some of the material submitted to DISR had not been visible to him until now.

Finally, the second ACSP member stated that she had not taken part in writing any of the reports or the Transition Agreement.

Invitation for Corrections and Feedback

I welcome constructive feedback on this article. If I have made any factual errors or drawn conclusions that are not supported by the evidence, I am committed to correcting them.

All I ask is that any proposed correction be accompanied by verifiable sources or documentation.

My goal is accuracy, transparency, and a shared understanding of how professionalization policy has unfolded — and I will gladly update this work if new evidence warrants it.

References

Below, you will find the list of all the materials referenced in this article:

-

Australia’s Cyber Strategy 2020, Department of Home Affair, 2020

-

Listening Before Leaping: AISA’s Cautionary Path on Professionalisation, Benjamin Mosse, May 2025

-

A Scheme For The Professional Recognition of Australian Cyber Security Professionals, Version 1, Tony Vizza, August 2022

-

Research Into Cyber Security Accreditation in Australia, AISA, September 2022

-

Provision of Cyber Security Workforce and Skills Forecasting, Contract Notice CN3794548, Australian Government, 2021

-

FOI 25/064/300132, Department of Industry, Science and Resources

-

FOI 300140 ACSP Documents, Department of Industry, Science and Resources

-

Stone and Chalk acquires AustCyber growth centre, James Riley, InnovationAus, February 2021

-

Michelle Price leaves AustCyber for EY following acquisition, Denham Sadler, InnovationAus, March 2022

-

Jason Murrell becomes Group Executive, AustCyber, September 2022

-

Non Disclosure Agreement Template, AustCyber

-

Introducing the Co-Design Team, AustCyber, May 2023

-

Co-design definition, Melbourne University

-

CYNAPSE: Benchmarking & Growing Australia’s Cyber Operations Workforce, Australian Government

-

FifthDomain launches cyber security skills program, Sasha Karen, ARN, June 2023

-

An Update on the ACSP Program, Australian Information Security Association, 2023

-

2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy Response, Australian Information Security Association, 2023

-

Understanding First, Solutions Second : A Systems Thinking Analysis of the Proposed Australian Cybersecurity Professionalization Scheme, Michael Collins, 2025

-

The Licensing Racket: How We Decide Who Is Allowed to Work, and Why It Goes Wrong, Rebecca Allensworth, 2025

-

Only 6 out of 220 recommended professionalisation to Home Affairs, Benjamin Mosse, April 2025

-

2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy, Home Affairs, November 2023

-

Growing and Professionalising the Cyber Security Industry Program, Australian Government, December 2024

-

Ministerial briefs regarding the grant to develop a professionalisation scheme for Cyber Security, from 1 June 2023 to 20 March 2025, Home Affairs, June 2025

-

Reconsider the Australian Government’s grant for professionalising the cybersecurity industry, Benjamin Mosse, January 2025

-

Words That Bind: How Professionalisation Speaks Us Into Silence, Benjamin Mosse, May 2025