Words That Bind: How Professionalisation Speaks Us Into Silence

25 May 2025In this essay, I analyze selected texts on professionalisation to expose the power structures they sustain. My intent is twofold: to invite those shaping these bodies to reflect on how their language may silence or sideline others - and to equip those who feel excluded with a sharper lens to see how language itself can become a quiet instrument of control.

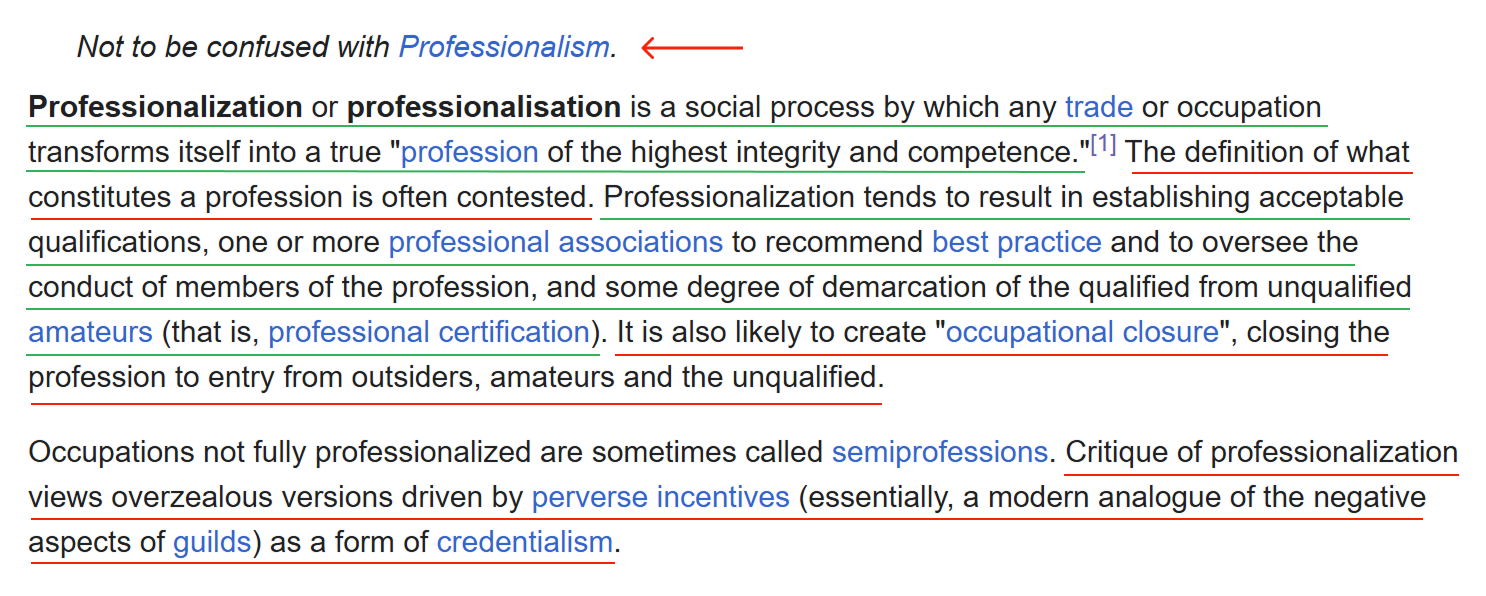

Wikipedia’s Definition of Professionalisation

Here is how Wikipedia defined professionalisation on 23 March 2025. I’ve added the arrow and underlines to help us examine the text more closely together.

Wikipedia is a collaborative encyclopedia that anyone can edit. I begin here not just for the content, but because this entry reveals the quiet power struggle beneath professionalisation itself.

Consider these points from the article:

-

Wikipedia insists that professionalisation should “not be confused with professionalism.” Why lead with this? Who made that decision, and what assumptions are smuggled in by drawing such a line?

-

The text contradicts itself. It describes professionalisation as elevating an occupation to “profession of the highest integrity and competence”, only to immediately call that very notion contested.

Wikipedia’s attempt to balance both sides reveals something deeper: professionalisation is not easily classified as “good” or “bad.” Its ambiguity is not accidental – it is inherent to the concept itself. Professionalisation resists clear definition because it is socially constructed, shaped by competing interests and shifting interpretations.

This flexibility allows professionalisation to mean many things to different people, yet it also prevents it from proving itself. Professionalisation asserts its own legitimacy, yet it cannot fully justify that legitimacy without relying on contested claims and unstable definitions.

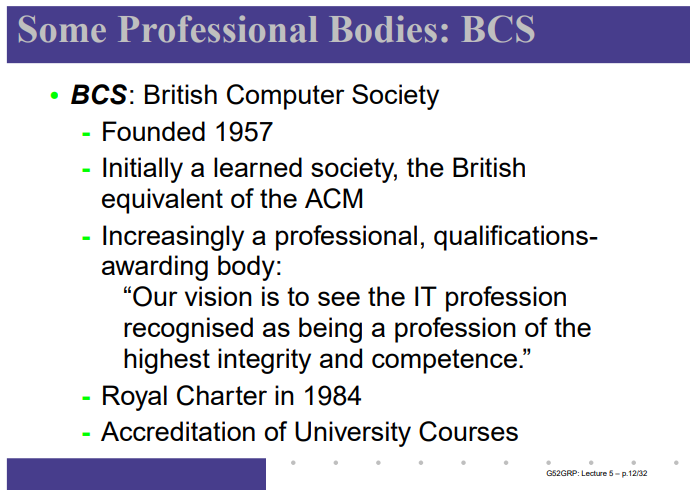

For the record, the first quote comes from the British Computer Society (BCS), who’s vision statement was, at some point in the past, to “see the IT profession recognised as being a profession of the highest integrity and competence”:

Compare that to how the quote is presented on Wikipedia. Do you see how much the proponents of professionalisation are struggling to justify it?

Now consider this: The British Computer Society (BCS) no longer presents a vision statement on its website. Its stated mission is now simply “to ensure everyone’s experience with technology is positive.”

Is this a convincing argument for professionalisation? I will leave that for you to decide.

AISA’s Newsletter of February 2025

On February 25, 2025, AISA informed its members that it had partnered with ACS and other industry partners to submit a proposal for the government’s cybersecurity professionalisation grant. Here is an extract from the newsletter:

The tensions surrounding professionalisation are evident in AISA’s newsletter. Concerns about professionalisation is acknowledged in just eight words, a token gesture, before the text quickly pivots to dismiss that view. Disagreement is framed as polarized (binary), with people either for or against professionalisation. Yet this framing distorts reality. Views on professionalisation are rarely fixed. They are complex, fluid, and often unresolved.

AISA’s own position reflects this instability. In 2022, after considering professionalisation, it chose not to proceed. Now, in 2025, with a new government grant on the table, it has reversed course.

Its own 2022 survey highlights this uncertainty. Twenty percent of respondents reported feeling “unsure” about professionalisation, a group that is acknowledged to be growing. Notably, the survey also showed that industry leaders are largely not supportive of professionalisation. Page 8 of the report makes this clear.

The newsletter reveals that AISA is fully aware of these divisions. The organisation now finds itself entangled in a power struggle, not only with vocal opponents but also with the quieter resistance of those who remain unconvinced.

This conflict reveals itself in the text, however briefly. The real challenge for AISA now is this: How can it promote professionalisation without appearing authoritarian or totalitarian?

To AISA’s credit, they organised a panel on professionalisation at CyberCon Canberra in 2025. I was invited to participate and debate openly, giving a small audience a chance to learn more about the issue. AISA is making an effort to show it can create and manage a professionalisation scheme that acknowledges and considers all voices and concerns – at least as much as that is possible.

Which of the other grant bidders has made any real effort to show they are not simply demanding control, but earning trust?

Australia’s Professional Standards Councils (PSC)

According to its homepage, PCS are the “independent statutory bodies responsible for promoting professional standards and consumer protection”.

This webpage provides their definition of professional standards schemes:

Here’s a summary of the text:

- A professional standards scheme limits the liability of association members if a court upholds a claim

- Associations must regulate members, meet reporting obligations, and improve standards to protect consumers

- Schemes can be renewed every 5 years

Here’ s a list of claims about professional licensing that are not mentioned on the web page:

- Improving gender diversity and inclusion

- Improving the quality of credentials

- Improving classroom education

- Increasing the availability and quality of teachers

- Reducing barriers to entry

- Solving skills shortages

- Retaining talent

- Enhancing domestic capabilities

There certainly exist arguments that a professional license might help with some of the desired outcomes listed above, however, PSC doesn’t confirm that. You can investigate this for yourself using a search query template like site:psc.gov.au “gender equality”.

In fact, the matter is worse: PSC has released reports that confirms that either these problems continue to exist despite professionalisation or can be caused by professionalisation.

For example, in 2022, PSC published a document called “Association Codes of Ethics: Part four Revising a code”, where it lists content to avoid in a code on page 18:

- Obligations dealing with corporate, employment and organisational matters

- Excessively expansive obligations for ‘appropriate’ behaviour

PSC confirms that Codes of Ethics can undermine liberty and reduce diversity:

Another example is PSC’s 2024 report called “Constructing Building Integrity: Raising Standards Through Professionalism”, in which builders report similar issues than the cybersecurity industry despite being professionalised:

-

Problems with the quality of education: “Table 1 shows that while most of the examined professionals require a tertiary education (bachelor and/or post-graduate degree) and additional training/CPD to become industry practitioners, the overall quality and robustness of qualification, education and training standards varies across the professions, potentially leading to competency tensions.” (p. 10)

-

Skills shortages: “Skills shortages and other barriers to entry to professional practice can also result in the professional being ‘stretched too thin’ to conduct work to a high professional standard” (p. 10)

Conclusion

In this essay, I have demonstrated how one might analyse the language used in texts about professionalisation. The techniques we explored are practical tools for uncovering power, contradiction, and manipulation through language.

-

First, we identified tension within a text – moments where the text contradicts itself. In both Wikipedia’s definition and AISA’s newsletter, we found a clear power struggle between supporters and critics of professionalisation.

-

Second, we used Socratic Questioning to challenge claims. By repeatedly asking “why?” and “where’s the proof?”, we exposed gaps in reasoning and unsupported assertions.

-

Third, we examined context. In AISA’s case, investigating its past stance on professionalisation revealed a significant shift in position, as well as a survey showing growing uncertainty and mixed industry support for accreditation.

-

Finally, we considered what a text omits – the unsaid. By examining PSC’s publications, we found a professionalised industry that still struggles with skills shortages, undermining claims that professionalisation alone can resolve such issues.

These techniques are now yours. Question, investigate, and reveal the truths that texts obscure. The more you apply these methods, the clearer you will see how language shapes power and influence.

Sources:

- Wikipedia, Professionalization

- Nilsson, Henrik “Professionalism, Lecture 5, What is a Profession?”

- Australian Information Security Association (AISA), Newsletter of February 2025

- Australian Information Security Association (AISA), 2022 Accreditation Survey

- Professional Standards Councils (PSC), What Are Schemes?

- Professional Standards Councils (PSC), Association Codes of Ethics: Part four Revising a code

- Professional Standards Councils (PSC), Constructing Building Integrity: Raising Standards Through Professionalism