The Benefits, Universality and Boundaries of DSRP Theory: Part 3 of 3

15 Dec 2025DSRP is one of the most useful frameworks I know for improving thinking. It helps you make cleaner distinctions, map systems, surface relationships, and compare perspectives.

But “useful” is not the same as “complete,” and “universal” is not the same as “all-explaining.”

In Part 2, I focused on why DSRP can be called universal: Derek Cabrera argues universality is a consequence of an entailment claim about identity, not merely an observation that the patterns ‘appear everywhere’. (1)

I’m aiming to stay as faithful as possible to the strongest version of the claim: DSRP is presented not merely as a thinking tool, but as a structural ontology that constrains what can count as a coherent identity or model. (1, 3) Under that framing, DSRP’s “predictions” are not time-stamped event forecasts; they are structural constraints and failure modes. (1, 3)

So the question here is not whether DSRP is powerful - it is. The question is: what does DSRP’s universality actually buy us, and where are the handoffs between structural grammar and domain content? Where does DSRP end and domain theory begin? Where can DSRP diagnose incoherence, and where can multiple coherent models still compete? And what would the strongest “world-side” interpretation need to add, beyond being a grammar of intelligibility?

That’s what follows: a boundary map of DSRP - stated in its strongest form, and then delimited as clearly as I can.

This post doesn’t attempt to restate the full ecology (e.g., the mechanics and calculus that Derek and Laura Cabrera argue generate the operators); it focuses only on what follows even if you grant the structural-ontology framing.

A Note on Terminology:

I’ll use the words ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ in two different senses:

-

Theoretical upstream: DSRP is “upstream” of domain sciences in the sense that it constrains the form of coherent specification (a structural grammar).

-

Practical downstream: In applied modelling, DSRP is “downstream” of domain work in the sense that your map’s content (mechanisms, parameters, evidence) must be supplied by domain theory and measurement.

So, DSRP may be upstream as structure, while good practice is downstream with respect to content.

Introduction

Before drawing any boundary lines, it helps to state the claim clearly.

The Cabreras’ strongest formulation is not that DSRP is only a helpful method for thinking (it is), but that DSRP functions as a structural ontology: a minimal set of structural requirements that any coherent “identity” (a thing, a model, a category, a theory) must satisfy. (3) On this view, DSRP is not competing with physics, biology, or psychology as a domain-specific causal theory. It sits upstream of them, closer to logic or mathematics: it constrains what can be coherently specified and modeled in the first place. (1)

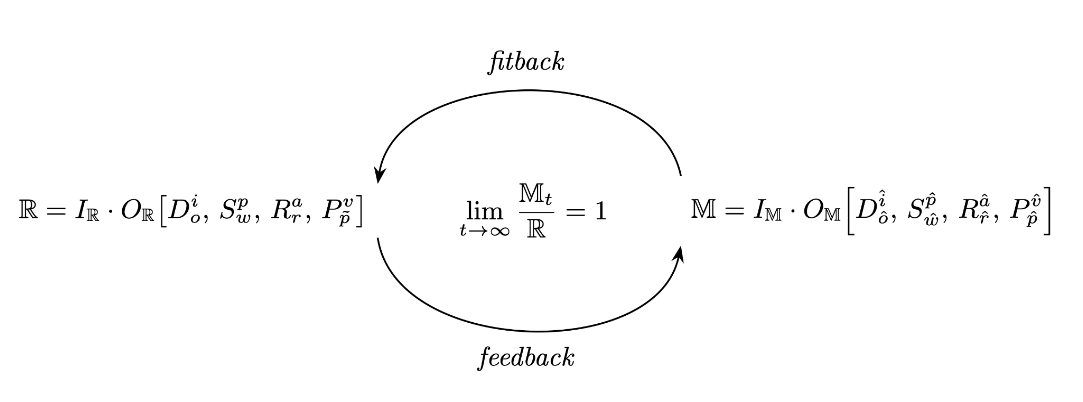

One more point matters for understanding what the Cabreras mean by “structural ontology”. The claim is not that DSRP adjudicates between competing domain theories. The claim is that organizational structure is empirically implicated in whether models can align with reality when ground truth is available. (4)

In controlled settings where the content is held fixed, changing the organization of that content produces systematic differences in measured model-world fit. On that framing, DSRP is a constraint on the kinds of models that can successfully align in the first place. (4)

Importantly, even on that strong framing, DSRP is not being presented as a theory that “explains everything” in the ordinary sense. As the authors put it, “DSRP doesn’t unify physics through a Lagrangian equation” (2) and “that doesn’t mean DSRP explains everything. But it structures everything that can be explained.” (2)

That line is the first major boundary: DSRP is about structure, not domain mechanisms.

It can help diagnose whether a model is missing essential structure (unmade distinctions, collapsed boundaries, undefined relationships, unacknowledged frames). But it does not, by itself, generate domain-specific causal mechanisms and calibrated quantitative predictions (the kind you need to predict which particle interactions occur, which biochemical pathway dominates, or what a market will do) - even if it offers a formal structural calculus.

With that framing in place, we can now map the boundaries that follow from it - where DSRP can do real diagnostic work (flagging structural incoherence and missing structure), and where it necessarily hands off to domain theory, evidence, and competing but coherent representations.

Boundary 1: DSRP constrains coherence, but it doesn’t replace domain theory

A clean way to state this boundary is:

-

DSRP can help diagnose structural incoherence and missing structure.

-

DSRP cannot, by itself, tell you the correct domain mechanisms, equations, or causal story.

This is not a criticism. It’s exactly what you should expect from a structural theory. Logic can rule out contradictions, but it can’t tell you whether the Higgs field exists. Information theory can constrain what is possible in communication, but it can’t tell you which codec a particular system will evolve. Likewise, DSRP can constrain what counts as a coherent identity or model, but it does not generate the detailed content of physics, biology, or economics.

The Cabreras state this boundary directly in their own terms: “DSRP doesn’t unify physics through a Lagrangian equation.” (2) In other words: even if DSRP is “upstream,” it is not a substitute for the mathematical and empirical machinery of domain sciences.

The positive claim they pair with this is also explicit: “That doesn’t mean DSRP explains everything. But it structures everything that can be explained.” (2) This is a strong statement, but it’s importantly not the statement “DSRP explains everything.” It is a claim about the structural preconditions of explanation and identity.

So the first boundary is a handoff rule:

DSRP can improve the organization of your explanations (and, in some settings, that organization is measurable in terms of model–world fit). Domain theory still supplies the mechanisms.

If you are working in particle physics, DSRP can help you keep track of primitives, boundaries, relationships, and frames (e.g., what you treat as “elementary,” what counts as an interaction, what is backgrounded in an effective field theory perspective). But it won’t derive the Standard Model. If you are working in biology, it can help you structure a model of selection pressures, organisms, environments, and perspectives of analysis - but it won’t replace genetics, ecology, or biochemistry.

This boundary matters because it implies a practical discipline for DSRP practitioners: DSRP does not remove the need for domain knowledge - it makes the need explicit. If you want a DSRP model to track reality (not just be structurally tidy), you must load it with the best available domain theory, data, and constraints. Otherwise, the model may be coherent while still being wrong, incomplete, or misleading. In that sense, good DSRP practice is downstream of domain understanding with respect to content: structure helps you think, but content is what your structure is actually about.

Boundary 2: Relativity - DSRP models are necessarily frame-dependent (so there is no single “final map”)

One of the most important boundaries in the DSRP as Universal Ontology paper is that the operators are not presented as “absolute” in how they appear in any given model. They are presented as context-dependent - their meaning and salience shift with scale and frame.

In the section titled Relativity, the authors write:

“No point, boundary, part, action, or view exists in isolation; each is meaningful only within a relational field.” (3)

And they make the implication explicit:

“This mechanic ensures that D, S, R, and P are not standalone operators but context-dependent ones.” (3)

They then spell out what “relative to context” means in practice, across the four operators:

-

For Distinctions: “what counts as identity or other depends on the frame of reference, the level of analysis, and the informational horizon…” (3)

-

For Systems: “part–whole relations vary with scale; what is a whole at one level becomes a part at another…” (3)

-

For Relationships: the “meaning of an action or reaction depends on the broader relational field…” (3)

-

For Perspectives: point–view structures “shift depending on context, vantage, accessibility of information…” (3)

This gives us the second boundary:

DSRP can constrain coherence, but it does not, by itself, generally yield a single canonical decomposition of a domain.

Instead, it forces something more honest: you must declare the frame (scale, horizon, vantage), because the identity/other boundary, part/whole boundary, salient relations, and point/view all depend on it.

If operators are context-dependent, then different frames can produce different (even competing) DSRP models while remaining structurally coherent. The job then becomes:

- Make the frames explicit,

- Check for structural incoherence, and

- Hand off to domain evidence and constraints to decide which framing best fits the purpose and reality-claims being made.

Boundary 3: Representation pluralism - DSRP doesn’t select a unique model even after you fix frame + content

Even if you do Boundary 1 correctly (load domain knowledge) and Boundary 2 correctly (declare your frame), there is still a deeper boundary: DSRP does not collapse the space of possible representations down to one “true” model.

The ontology paper repeatedly emphasizes that DSRP is structural and content-agnostic:

DSRP “specifies the generative grammar by which information organizes, without making any claims about the particular information in question” (3)

That matters because a content-agnostic structural grammar can constrain coherence while still leaving room for multiple workable encodings of the same domain (graphs, hierarchies, narratives, equations, simulations).

Practically:

-

You can represent the same situation as a causal graph, a hierarchy, a set of categories, a network, a process model, a state machine, a narrative, or an equation-driven model - and multiple representations can be structurally coherent under DSRP while emphasizing different invariants, tradeoffs, or manipulable variables.

-

DSRP can help you spot missing structure (unstated distinctions, collapsed boundaries, implicit perspectives), but it will not tell you which representation is the correct one.

So there is a third “handoff” that’s easy to miss:

Domain knowledge selects content. Frame selection sets context. But representation choice is still an extra step - decided by purpose, tractability, measurement constraints, and empirical performance.

That is a real boundary: DSRP can help you avoid incoherent representations, but it cannot, by itself, choose among coherent ones.

Boundary 4: DSRP can diagnose incoherence, but it doesn’t (by itself) decide “what exists”

At this point, the boundaries stack into a useful picture:

- Boundary 1: DSRP doesn’t replace domain theory (content still comes from the domain).

- Boundary 2: DSRP models are frame-relative (no view-from-nowhere).

- Boundary 3: Even with fixed content + frame, DSRP doesn’t select a unique representation.

Now we can name the boundary that sits underneath many ontology debates:

DSRP can adjudicate structural identity/coherence claims (what must be true for an ‘identity’ or model to be intelligible), but it does not settle domain-level inventories where multiple coherent ontologies/models remain live.

The ontology paper gestures at this distinction in a compact way when it describes DSRP as “structural rather than categorical.” (3)

The force of that phrase is that DSRP constrains the form of intelligible identity (what any model must contain structurally), not the particular inventory of entities a domain theory posits (e.g., whether ‘wavefunction collapse’ is a real process vs an update rule; whether ‘fitness’ is a causal property vs a statistical summary; whether ‘utility’ is real vs instrumental).

Derek Cabrera goes further and argues that once the structural operators are formalized, ontology and epistemology “dissolve” into one structural fabric:

“Once this structure is formalized, the boundary between ontology (what exists) and epistemology (how we know it) dissolves …” (3)

My claim here is narrower: even granting that move, DSRP still doesn’t uniquely select between empirically competitive domain ontologies.

A useful nuance is that pluralism doesn’t mean equal fit. Multiple models can be structurally coherent and still differ in how well they align with reality. On the Cabreras’ empirical framing, organization is one driver of that difference (even when the underlying informational content is comparable). So DSRP may not pick a single “final ontology,” but it can still matter in a stronger way than “tidiness”: it can change measured alignment.

Even if DSRP is correct as a structural ontology, the following remains possible:

- two theories can both instantiate D/S/R/P cleanly,

- both can be structurally coherent,

- both can even be empirically competitive for a time,

- and yet they can disagree about what exists (what the primitives are, what is real vs instrumental, what is fundamental vs emergent).

In those cases, DSRP still helps - but in a specific way:

-

it makes the structure of the disagreement explicit (which distinctions are doing the work, which boundaries differ, which relationships are asserted, which perspectives are assumed),

-

it can expose covert incoherence (models that forbid the very structural conditions they rely on),

-

but it does not eliminate the need for domain evidence, new tests, and explanatory comparison to decide between coherent rivals.

This isn’t a weakness. It’s a boundary condition of any structural framework: coherence is necessary, but it is not sufficient for truth.

As a practitioner, treat DSRP as a coherence and clarity engine, but don’t confuse “a coherent map” with “the correct ontology.” When the question is “what exists?” you still need the hard work of domain theory, measurement, comparison, and arguments.

Boundary 5: The falsifiability target is structural, not “does X exist?”

The ontology paper makes a very specific move on falsifiability: it says DSRP is “structural rather than categorical,” so falsification does not primarily apply to the existence of particular entities (electrons, genes, firms), but to whether organized phenomena can exist without the minimal operators and their invariants.

They state this boundary plainly:

“Because the ontology advanced here is structural rather than categorical, falsification applies not to the existence of particular entities, but to the presence or absence of the minimal organizational operators and mechanics that make any entities possible.” (3)

And they sharpen it further:

“DSRP would be falsified if organized phenomena were discovered that violated the structural invariants defined by the operators …” (3)

They then list conditions under which this would occur, starting with the strongest:

“A natural system is identified that exhibits coherent, organized behavior without any discernible Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, or Perspectives, nor any isomorphic polarity structure…” (3)

On the authors’ framing, this shifts what counts as a “test” of the ontology claim:

- It is not tested (or refuted) by pointing to a disputed entity in a domain theory.

- It is tested by finding a counterexample where organization arises without those operators (or any isomorphic dualities).

So the boundary is: even when DSRP is framed as falsifiable, the falsification criteria sit at a much higher altitude than most day-to-day scientific disputes. It targets the structure of organization itself, not the moving frontier of which entities or mechanisms a domain currently posits.

For practitioners, use DSRP as a structure check, not a truth machine. If your model is failing in the real world, first ask: What distinction is missing? What boundary is wrong? What relationship is assumed but untested? What perspective is implicit? Then go back to the domain: measure, test, and update the content.

Boundary 6: The discovery boundary - DSRP can become self-sealing unless you deliberately challenge your modelling choices

The previous boundaries show where DSRP hands off to domain theory, frame declarations, and representation choice. This final boundary is different: it’s about how DSRP practice can fail even when the model is coherent.

Because DSRP is a structural grammar, it is extremely good at making models make sense. That strength creates a risk: a coherent DSRP map can become a closed world that protects its own assumptions.

The danger looks like this:

- You choose initial distinctions (what counts as identity vs other),

- you set boundaries (what’s in scope vs out),

- you pick a frame (scale, horizon, vantage),

- you choose a representation (graph, hierarchy, process model),

- and then you use DSRP to make that structure internally consistent.

At that point, DSRP can help you build a very coherent model - while still missing the key discovery: that your starting distinctions and boundaries were wrong.

This is a genuine boundary because it marks the line between:

- DSRP as a coherence engine (tidy, intelligible maps), and

- DSRP as a discovery-capable practice (maps that can be surprised by reality).

The practical fix: treat modelling choices as hypotheses, not axioms.

To stay discovery-capable, DSRP practitioners have to deliberately do something that DSRP will not do automatically: challenge the framing inputs.

This is not unique to DSRP. In general, structured practice regimes are designed to reduce premature closure; the Cabreras’ broader training/ecology appears aimed in that direction as well.

A simple discipline is:

-

Run frame-variation deliberately. Build 2–3 alternative framings that change one thing at a time:

- a different identity/other cut,

- a different system boundary,

- a different time horizon or scale,

- a different “point/view” (stakeholder, measurement lens).

-

Ask what becomes easier or harder to explain. Which framing makes the fewest special assumptions? Which framing predicts failure modes you actually observe?

-

Let domain evidence select. Use data, mechanisms, and tests to decide which framing tracks reality better—rather than letting coherence alone decide.

This is the “meta-boundary” behind all the others: DSRP can’t guarantee that your starting ontology is the right one. It can only help you make the consequences of your starting choices explicit.

Conclusion: a boundary map, not a takedown

Taken together, these boundaries clarify what DSRP’s universality actually buys you.

DSRP is powerful because it forces structure into the open: distinctions, boundaries, part-whole structure, relationships, and frames. Under the strongest framing, it can constrain coherence - flagging models that collapse under their own structural requirements.

But these boundaries also clarify the handoffs:

- Domain theory supplies mechanisms and equations (DSRP doesn’t replace them).

- Frames must be declared (no view-from-nowhere).

- Multiple coherent representations can coexist (DSRP doesn’t pick a unique encoding).

- Coherence is not truth (what exists is still settled by domain evidence and comparison).

- Falsifiability is structural (tests live upstream of most entity-level disputes).

- Discovery requires frame variation (otherwise coherence becomes a cage).

If you want to apply DSRP rigorously, treat it as a disciplined workflow:

- Load the best domain constraints you have

- Declare your frame (scale, horizon, vantage)

- Choose a representation that matches the purpose

- Use DSRP to stress-test coherence

- Compare coherent rivals using evidence and outcomes

- Vary the framing inputs periodically to stay discovery-capable

That is the boundary map: DSRP structures explanation. It does not terminate explanation. The termination point - what survives - still belongs to domain theory, measurement, and the world.

References

-

A conversation with Derek Cabrera about DSRP Ontology, December 2025, Benjamin Mosse and Derek Cabrera

-

The Grammar of Reality, May 2025, Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera

-

DSRP as Universal Ontology: The Structural Foundation of All Systems, November 2025, Derek Cabrera

-

The Structure of Thought and Reality : Empirical Evidence for the Three Universal Laws Linking Mind, Matter, and Meaning, October 2025, Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera

Thank you for reading. If any errors or misunderstandings appear in this article, they are entirely my own and should not be attributed to Derek and Laura Cabrera or their work.