A conversation with Derek Cabrera about DSRP Ontology

23 Dec 2025I’m grateful to Derek Cabrera for taking the time to read my post and respond in detail. Whatever our disagreements, I value direct engagement with ideas - especially when a theory makes ambitious claims about ontology.

I’m publishing our exchange in full for two reasons:

First, it makes the points of agreement and disagreement explicit, in Derek’s own words, rather than through my paraphrase.

Second, it gives readers the context needed to understand what Derek means by terms like “structural ontology,” “constraints,” and “falsifiability” in DSRP.

At the time of our initial exchange, a key “DSRP-as-ontology” paper Derek referenced was not publicly discoverable or readily accessible online through ordinary scholarly channels, which created avoidable confusion about what claims were being made and where. Derek later pointed me to the paper once it was available, and it added important context.

What follows is our conversation, presented as-is (edited only for formatting), so readers can evaluate the arguments and the framing for themselves.

If you want to understand what DSRP’s ontology claim is actually saying - where its boundaries are, how it’s meant to be interpreted, and what work it’s intended to do - I think Derek is right about one thing: read the referenced paper and, where possible, load the broader ecology of linked work, because the meaning of these claims depends on how the pieces fit together.

The Conversation

Message 1: Benjamin contacts Derek and Laura Cabrera for comments - 19/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek and Laura,

I’ve just published a three-part series on the benefits, universality, and limits of DSRP Theory. If you’re open to it, I’d really value your thoughts on Part 3 in particular, where I engage critically with some of your recent scientific papers.

If you’re interested, I’d also welcome a conversation - happy to discuss where you think my critique misses the mark, and where it might point to useful refinements or open questions.

https://www.benjamin-mosse.com/2025/12/15/universality-and-the-limits-of-dsrp-theory-part-3.html

Thank you for considering it.

Kindest regards, Benjamin

Message 2: Derek responds to Benjamin - 19/12/2025 AEDT

I want to start by saying I love and welcome critical engagement — especially when a theory makes bold claims. That’s appropriate, healthy, and necessary. Where we often go wrong, though, is how critique is applied.

Good science doesn’t start with critique. It starts with deep systemic understanding. Steel-man first. Then critique. And only then, if necessary, rejection. Critique without first demonstrating structural comprehension isn’t rigor — it’s just skepticism.

That standard matters even more today because we’re operating in an unusual epistemic moment. In the age of AI, the world’s information is effectively at our fingertips, and it’s now possible to generate relatively thorough — though often incomplete — analyses of almost any paper or theory very quickly. That makes breadth easy. What it does not guarantee is ecological understanding: awareness of the full body of related work, the developmental trajectory of the theory, and the interdependence of results across papers, methods, and domains. For theories making ontological claims, that ecology matters.

In practice, theorists who work every day within a theory have often heard criticism X before and, as a result, pursued experiments or written proofs to resolve it. That work may live in a narrower or less visible paper that a critic (or an AI) simply doesn’t have loaded — and therefore doesn’t appear in the critique. My suggestion is simple: ask the scholar for the ecology of papers that “complete the circle,” load all of them into AI (or read them), and then see what critique you or the AI has. I’m happy to do this — though it would be somewhat comical to see what happens when the same standard is applied consistently to other theories in the arena.

This matters because in science we are almost never saying “theory X is perfect.” What we might say, if we’re lucky, is “theory X is better than the alternatives.” I am confident in that claim here — based on the evidence.

That standard matters even more because DSRP makes explicit ontological claims. Those claims should raise the bar. But that bar has to be applied consistently.

For example, if we applied the same ontological, predictive, and falsifiability standards being invoked here to other proposed ontologies or thinking frameworks — including classical philosophical ontologies, modern analytic or process ontologies (e.g., Aristotle’s or Kant’s Categories, Husserl’s phenomenology, Whitehead’s process philosophy, Quine, Bunge’s formal ontology, ontic structural realism, mereology, and other forms of process metaphysics), or the dominant systems-thinking frameworks (e.g., SD, CST, VSM, Cynefin, GST) — most would fail immediately on multiple fronts. Many make no necessity claims, provide no minimal axioms, specify no falsification conditions, and offer no cross-domain entailment logic. So critique is welcome — but it must be symmetrical.

That said, I love a good fight and I’m happy to take the heat, even when it isn’t applied to “competing” theories. And for context: you will not find anyone more critical of DSRP than me. I know exactly where its warts are.

It’s also important to be precise about what kind of theory this is. DSRP is not “just philosophy.” It has a substantial empirical literature demonstrating effects: controlled studies show that explicit use of DSRP produces measurable improvements in systems thinking, metacognition, learning transfer, problem solving, and related outcomes. That alone places it beyond most so-called “thinking frameworks.” You are also right that my claims go beyond thinking and into ontology.

At the same time, DSRP is not a domain-specific causal theory competing with physics or biology. It is a structural ontology. Structural ontologies do not adjudicate between rival empirical theories; they specify the conditions under which any coherent identity, model, or theory can exist at all. Logic doesn’t tell you which hypothesis is true either — but that doesn’t make logic merely descriptive.

With that framing, here is a concise response to the specific issues raised.

(1) “DSRP is descriptive, not adjudicative.”

Correct — and that is a feature, not a flaw. The same is true of logic, mathematics, information theory, evolution, and other structural theories: they do not judge which empirical claims are true or which hypotheses should be accepted. Instead, they constrain what can be coherently described, modeled, tested, or explained in the first place.

DSRP operates at that same structural level. It does not replace empirical testing or adjudicate between competing explanations. What it does do — and does extremely well — is diagnose structural coherence. Because it is neutral with respect to content, values, and conclusions, it can reliably expose internally incoherent structures: missing distinctions, broken or circular relationships, collapsed systems, unacknowledged perspectives, and other forms of structural instability. In practice, this often makes incoherent or untenable models visible very quickly — not because DSRP “disagrees,” but because the structure itself does not hold together. Importantly, this diagnosis can be done predictably and consistently in computational models, not merely in the minds of human users.

That neutrality is precisely what makes DSRP objective. It constrains intelligibility without dictating outcomes. It identifies when a model cannot possibly work as structured, while leaving empirical adjudication — what is actually the case — to domain-specific evidence and testing. Most importantly, awareness of the subjectivity of reference framing (perspective) is built into the ontology itself — the closest approximation to objectivity we have.

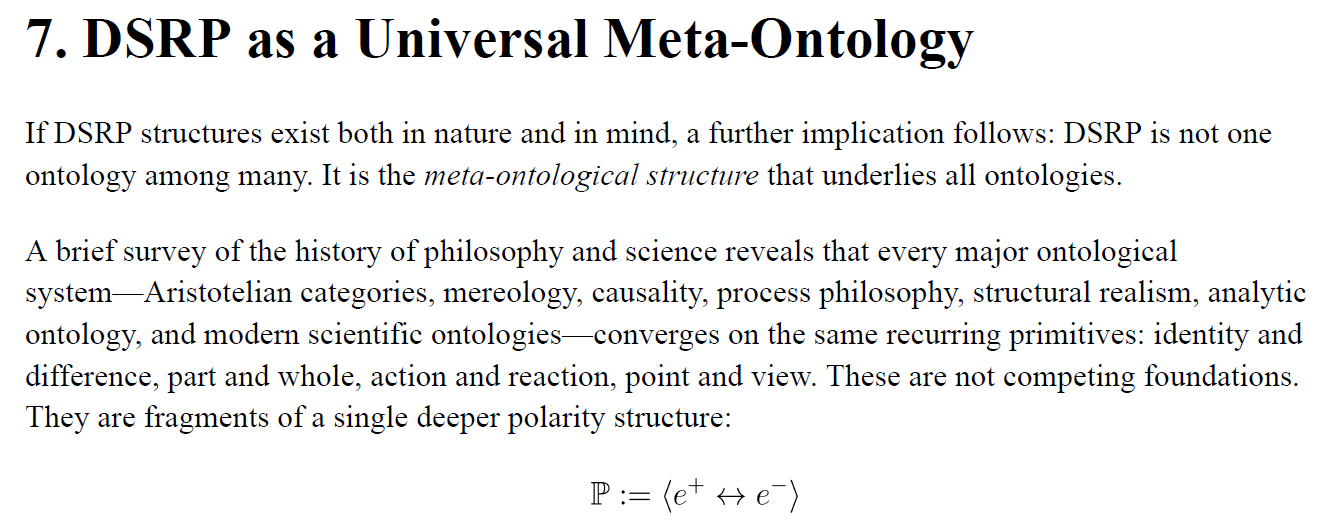

(2) “Universality doesn’t imply ontology.”

Agreed in general. But the claim here is not inductive (“it appears everywhere”). It is entailment-based: identity cannot exist without Distinction, System, Relationship, and Perspective. Remove any one and identity collapses into incoherence or indeterminacy. A single coherent counterexample would falsify the theory.

(3) “The necessity proof isn’t complete.”

After Enclosure (see paper), D, S, R, and P are derived as jointly necessary and jointly sufficient for identity, with an explicit argument for minimality (no fewer, no more). What remains is translation into different formal idioms for different audiences — not missing substance.

(4) “DSRP doesn’t predict.”

It doesn’t predict events — and this too is a feature, not a flaw, especially given the field’s near-total fixation on events and surface-level information. DSRP predicts underlying structural constraints and failure modes — the same kind of prediction made by logic, thermodynamics, information theory, and natural selection. Systems that suppress one or more of D, S, R, or P reliably produce brittleness, paradox, polarization, and breakdown. That prediction is falsifiable — and repeatedly confirmed.

(5) Falsifiability.

Remarkably, DSRP is relatively easy to falsify. It would be falsified by a single coherent identity that exists without Distinction, System, Relationship, or Perspective — without reintroducing them at a higher level of description. No such example has been produced. One would end the theory immediately. This is the same entailment-based falsifiability we see in theories like evolution.

(7) “The claims are too bold / adoption is uneven.”

Boldness — and the pace or pattern of adoption — is not itself a critique of a theory. In science, uptake is a sociological variable, not a truth condition. The history of science shows that even well-supported theories can diffuse unevenly, especially when they are foundational, cross-disciplinary, or challenge established evaluative norms.

That said, it’s worth noting that DSRP has in fact seen substantial adoption across education, organizational practice, systems training, and applied research. Its use in classrooms, leadership development, military and intelligence contexts, therapy, AI, and empirical studies demonstrates that the theory is neither marginal nor purely speculative. At the same time, like any theory operating at the level of ontology, its diffusion is necessarily slower and more uneven than domain-specific tools.

What matters scientifically is not whether a theory is comfortable, familiar, or universally adopted, but whether it is coherent, falsifiable, empirically grounded, and explanatory relative to the alternatives. On those criteria, DSRP stands or falls independently of its current adoption curve. Uptake can inform relevance and utility, but it does not adjudicate validity.

Some of this is necessarily technical. Structural ontologies operate upstream of familiar empirical theories, and that takes work to see clearly. But the burden cuts both ways: if we’re going to critique claims at that level, we owe them not just surface familiarity, but engagement with the full ecology of evidence — empirical studies, formal results, proofs, and how they fit together over time.

In short: critique is not only welcome — it’s necessary. But it should be systemic before critical, applied symmetrically, and grounded in what has actually been demonstrated — empirically and structurally — not just what can be quickly assembled from isolated sources.

Message 3: Benjamin responds to Derek - 20/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek,

Thank you for responding.

I want you to know I have read your work in the Journal of Systems Thinking and elsewhere, including the DSRP Primer. The papers I leaned on most for the ontology question were The Grammar of Reality, The Unified Calculus of Organization, Structure, Emergence, and Meaning: The Patterns that Connect Mind and Nature, and O Theory: The Science of Organization.

I also wrote Parts 1 and 2 to present DSRP in its strongest form.

https://www.benjamin-mosse.com/2025/12/14/universality-and-the-limits-of-dsrp-theory-part-1.html

https://www.benjamin-mosse.com/2025/12/14/universality-and-the-limits-of-dsrp-theory-part-2.html

Based on your reply, here is what I think we agree on: DSRP is descriptive, not adjudicative. And universality does not by itself establish ontology. When I say universality, I mean a universal grammar of description.

Regarding point (3), “The necessity proof isn’t complete”, I think there’s a misunderstanding. I agree with your response that explains the co-implication and simultaneity dynamics between the patterns/elements of DSRP Theory.

My point is that an ontological theory must meet the following criterion:

- Rule out some possible world-structures,

- Derive non-trivial consequences we wouldn’t otherwise expect, or

- Discriminate between rival ontologies via distinctive predictions.

Regarding point (4), “DSRP doesn’t predict”, I don’t agree with changing the definition of what a “prediction” is in science. If DSRP is indeed an ontological theory, then it must be capable of making at least one new quantitative prediction.

I’ve not made reference to the following, so I’m not sure how to interpret these parts of your response:

(5) “Falsifiability”

(6) “The claims are too bold / adoption is uneven”

Thank you.

Benjamin

Message 4: Derek responds to Benjamin - 20/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Benjamin,

I appreciate the engagement and the time you’ve taken with the work. That said, I think it’s worth noting that critiquing a theory at the level of ontology really does require loading the full technical and empirical ecology of that theory. Without that, it’s easy to end up debating definitions rather than results. Some additional training or deeper engagement with the later-stage work may be helpful before diving quite this far into the deep end. I would also suggest real skills training. Science is ultimately practical —it lets us do things we couldn’t otherwise do. The training camp belts will help you take your skills to a higher level and see how the science plays out ontologically—not in the abstract and philosophical sense of the term ontology but in the real world skills and results that are hard to argue with.

At some point, ontology debates have to terminate in evidence and comparison. That’s what we did. We evaluated the most widely used ontological frameworks — including Aristotle’s and Kant’s Categories, Husserlian phenomenology, Quinean ontology, Bunge’s formal ontology, ontic structural realism, mereology, and process metaphysics — against explicit, science-based criteria. That analysis is published, transparent, and open to challenge.

Under those criteria, DSRP performs better.

If someone disagrees, the scientific options are straightforward: challenge the criteria, challenge the scoring, or present an alternative ontology that performs better under explicit criteria.

Message 5: Benjamin responds to Derek - 22/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek,

Would you be willing to share the exact citation(s) (title, venue, and URL/DOI) for the paper(s) where you evaluated Aristotle’s/Kant’s Categories, Husserl, Quine, Bunge, mereology, ontic structural realism, and process metaphysics against DSRP using explicit science-based criteria?

I haven’t been able to locate those references in the PDFs I downloaded from the Journal of Systems Thinking and elsewhere, and I want to make sure I’m reading and engaging the exact analysis you’re pointing to.

If you can also share the criteria and scoring table (or where it appears), that would help me engage it precisely.

My current understanding of where we largely align is:

(1) DSRP is descriptive rather than adjudicative (it doesn’t by itself choose between rival empirical theories)

(2) Universality of a descriptive grammar doesn’t automatically establish ontology without an additional bridge argument

(3) As a structural ontology, DSRP doesn’t select which empirical theory is true; domain evidence and tests do that.

Where I’m still unclear is the specific constraint/falsifiability claim. If DSRP is entailment-based (as you put it), then it should support at least one non-trivial impossibility claim.

Could you give one concrete example of an “identity” that cannot exist without Distinction, System, Relationship, and Perspective, and what would count (in your terms) as a coherent counterexample that would falsify that necessity claim?

Because others are reading this exchange, I’m planning to update the post to make your “structural ontology” framing explicit up front, once I’ve read the comparison paper(s) you referenced.

Thank you.

Benjamin

Message 6: Derek responds to Benjamin - 22/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Benjamin,

A couple of quick clarifications and then a suggestion for next steps.

1- Where the analysis actually lives

All of the work you’re asking about (ontology, calculus, Enclosure, emergence, O-Theory, VMCL, etc.) is already collected in Training Camp under Bibliography, and summarized in plain language in the Science Summary section.

The specific comparative ontology analysis you’re asking for—where Aristotle’s and Kant’s Categories, Husserl, Quine, Bunge, OSR, mereology, and process metaphysics are evaluated alongside DSRP against explicit science-based criteria—is in the DSRP-as-ontology paper (see the table with criteria and scores). That’s the place to engage the claim, not my shorthand in a comment. And, as with any research program, it’s the ecology of papers taken together that makes the case, not any single article in isolation.

2- Where we actually don’t align

The three bullets you listed aren’t quite how I’d frame things:

(1) “DSRP is descriptive rather than adjudicative.” DSRP is structural/ontological. It doesn’t choose between rival domain theories, but it does adjudicate structural coherence. It’s not “just descriptive”; it imposes hard constraints on what can count as a coherent identity or theory.

(2) “Universality of a descriptive grammar doesn’t automatically establish ontology.” I don’t base the ontology claim on universality. The core argument is entailment/minimality: identity cannot exist without D, S, R, and P. Universality is a consequence of that, not the premise.

(3) “As a structural ontology, DSRP doesn’t select which empirical theory is true; domain evidence and tests do.” Partly. Domain evidence chooses between empirically equivalent theories, but DSRP can and does rule out structurally incoherent ones regardless of empirical fit. So it’s doing more work than your summary suggests.

3- Falsifiability / impossibility

The core entailment claim is simple, and it’s spelled out in the Enclosure + calculus work (and backed by a lot of empirical studies): No coherent identity can exist without Distinction, System, Relationship, and Perspective.

A counterexample would be a fully specified “thing” that:

–isn’t distinguished from anything else,

–has no part–whole structure at any level,

–stands in no relations whatsoever, and

–is not relative to any point of view or frame.

And crucially: it has to meet all four of those conditions without smuggling DSRP back in under a different description.

If someone can construct and defend that, the ontological claim fails. To my knowledge, no one has.

4- Fair standards and parsimony

It’s also worth saying out loud that if we apply this same basic litmus test to other popular “ontologies” and systems-thinking / thinking frameworks, most don’t even make it to the starting line. They don’t specify necessary structures, they don’t offer minimality claims, they don’t state falsifiability conditions, and they aren’t operationalized in a way that allows comparative testing. In that sense, DSRP is unusual simply for being willing to stand in that light at all.

From an Occam’s point of view, DSRP also makes a very strong parsimony claim: four patterns, jointly necessary and jointly sufficient—no more and no less. If someone wants a richer ontology, that’s fine, but then they need to show why the extra machinery is necessary and what it explains that DSRP cannot. Whatever standard we use for a “good ontology” should be applied fairly across the board; it can’t be something that quietly exempts the classics and only falls hard on DSRP. Parts of your current critique slip into exactly that asymmetry.

5- Next steps

You’re absolutely free to write whatever you like on your own blog. On Camp, though, it’s worth saying that what you’re asking about here is very high-altitude work—basically Purple/Black-belt territory. We don’t even introduce most of this research until later belts because, even when we make it as accessible as we can, it still takes time and practice to really see what’s going on.

Nearly 25 years ago we realized that the science itself was solid, but the accessibility wasn’t. So we started focusing just as much on the science of practice: what people should do, in what order, and at what level of complexity. The field does a lot of talking about “systems thinking,” but talking about ST is very different from being able to actually do it at a high level. The ontology question isn’t just a matter of language; it shows up in how people think, model, and act in real contexts. We learned the hard way that if you have people drink from the firehose on day one, they get exhausted and leave. The belt sequence and Training Camp design are based on that learning, not on hiding the research (which we make available at the outset).

Right now you’ve done the WB and some reading, which is great. But before going much further with public “limits of DSRP” critiques, I’d strongly recommend working through the belt sequence and the Science Summary/Bibliography so you’re arguing from inside the ecology and from actual practice, rather than from high-level overviews and a handful of papers. Critiquing a theory at the level of ontology really does require that full ecology.

Happy to keep answering questions here as you work through it, but that’s the path I’d suggest.

Message 7: Benjamin responds to Derek - 23/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek,

Thank you for the detailed response.

I appreciate the clarification on how you’re framing DSRP (structural/ontological, adjudicating coherence rather than selecting among domain theories), and I’m happy to engage that framing directly.

One quick meta-point, because I think it’s driving some misunderstanding: my intent isn’t to “take down” DSRP.

I’m trying to make its limits explicit as part of a 3-part reflection on DSRP.

In my view, limits are part of what makes a framework scientific and practically useful. Where I’m pushing is specifically on claims that DSRP does more than it demonstrably does (e.g., “how being arises,” “this is physics,” etc. from the Grammar of Reality as just one example). If those are meant in a technical structural sense, I want to represent that accurately.

Three concrete requests so I can engage precisely and update the post fairly:

1) Citation / artifact

The Bibliography mentions a paper called “DSRP as Universal Ontology: The Structural Foundation of All Systems.” but I can’t find it anywhere in the Journal of Systems Thinking (even though it’s referenced to have been published there in 2025).

It’s also not listed on other websites like Google Scholar and so on.

Where can I get a copy of that paper?

2) Scope + limits (what DSRP can and can’t do)

I accept that DSRP doesn’t choose between empirically equivalent domain theories.

My question is narrower: when you say DSRP “imposes hard constraints on what can count as a coherent identity or theory,” can you provide one worked example of that constraint in action - i.e., a model/identity that appears viable on its own terms, but which DSRP rules out as structurally incoherent, along with the operational criterion used (and what would count as a false positive)?

3) Falsifiability

Relatedly, on falsifiability: you’ve described the counterexample as an “identity” with no D/S/R/P at any level.

I’m not disputing the logic of that as stated - I’m trying to understand whether this is being presented as:

(a) a constitutive claim about what it means to specify an identity/model at all, or

(b) a substantive claim about the structure of mind-independent reality.

If it’s (a), then the “limit” I’m highlighting is exactly that DSRP functions as a grammar of intelligibility rather than a generative causal theory - and I’m fine with that, provided the ontological rhetoric is interpreted accordingly. If it’s (b), then the burden is higher and the comparison table + operational examples become even more important.

Once I have the paper and one concrete coherence-adjudication example, I’ll revise the post so your “structural ontology” framing is stated upfront, and so the discussion is about the correct claim rather than shorthand.

Thanks again,

Benjamin

Message 8: Derek responds to Benjamin - 23/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Benjamin,

You’ve taken on a pretty big project: trying to map the limits of DSRP before really working through the theory and its ecology. You can always do that at a surface level, but it will always be partial. The deeper the underlying structure is understood, the more meaningful any “limits” discussion becomes.

Just to be clear: I’m not especially invested in whether you change your blog or not. There are plenty of unfair or straw-man accounts of DSRP out there—that’s par for the course with any theory that makes strong claims. What I am committed to is transparency in the science. If someone is asking genuine questions, I’ll do my best to clarify what the theory actually says and what the evidence is.

1) Citation / artifact

The paper you’re looking for is:

Cabrera, D. & Cabrera, L. (2025). “DSRP as Universal Ontology: The Structural Foundation of All Systems.” Journal of Systems Thinking .

It’s in the Training Camp Bibliography now.

2) One concrete coherence-adjudication example

Here’s a simple structural example of what I mean by “imposes hard constraints” and how DSRP can rule something out. This is from our book Connect the Dots.

Take basic network/graph theory. In its simplest form, you have:

Nodes (A, B, C, …)

Edges (relationships) between nodes, like AB, AC, etc.

Formally, an edge is a relation between its endpoints. The edge AB doesn’t exist “off by itself”; it only makes sense as a connection between A and B. A “graph” with edges but no vertices isn’t a weird kind of graph, it’s not a graph at all under the definition.

Euler’s bridges problem is a nice concrete example. The land masses are the nodes; the bridges are the edges. In the real world, each bridge is also an identity (a thing with parts). In the graph, that same bridge is a relationship between two nodes. Either way, you don’t get the relationship without:

Distinguishing the land masses and bridges (Di),

Seeing each as a system with parts (Spw),

Treating “connected to” as a relationship (R), and

Framing which units are in focus and which are background (Pv).

In DSRP terms, you can have relationships between anything—objects, systems, even other relationships. DSRP has no problem with “relations between relations.” But for any relationship to exist or be modeled at all, some structure has to show up:

Something has to be distinguished: this node vs that node, this edge vs that edge, “this side” of the relation vs “that side.”

There is part–whole structure: even a “single” relationship is at least a whole made of parts (two ends, an action and a reaction, two roles in an interaction).

There is a perspective or frame of refernce: we’re taking the relationship or the nodes as identity and everything else (the background “space”) as other. Or, the land could be an edge between two bridge nodes for that matter.

Relationships don’t float in a void. They always come with D, S, and P built in somewhere, even if we don’t name them.

So if someone says “there are only relations, and absolutely no ‘things’ or distinctions anywhere,” that ends up sawing off the branch it’s sitting on. It’s like saying “I want a graph with only edges and no vertices at all.” Under the formal definition, there is simply no such graph: you’ve removed the very conditions that make “edge” meaningful.

Operationally, the constraint is: Whenever a model posits relationships (edges), there must be some level at which the relata (nodes, or other units) are distinguished and the relation has internal parts and a frame. If it forbids that across the board (“edges only, no vertices ever”), it collapses into incoherence.

DSRP is just making that kind of structural requirement explicit and general: R always drags D, S, and P along with it, whether we admit it or not.

3) Falsifiability: (a) vs (b)

On your last question, the answer really is “both,” but in a straightforward way.

On one side, DSRP is giving the basic conditions for something to even count as an identity or a model at all. When I say “constitutive,” I don’t mean anything mysterious. I mean: if you strip away all distinctions, all part–whole structure, all relationships, and all perspective, you don’t get a very simple “thing,” you get no thing. There’s nothing left to point to, describe, or reason about. It’s like trying to have a graph with no vertices, or chess with no rules—you haven’t got a very minimal instance; you’ve lost the thing itself.

On the other side, I’m also making a world-side claim: mind and reality share the same organizational patterns (𝕄 = I·O, ℝ = I·O), and DSRP describes that shared structure. That’s what O-Theory, the MIO paper, and the existence/effect studies are about—showing that these patterns are not just in how we talk, but also in how mind and nature are actually organized.

So yes, DSRP is a structural ontology, not a domain-specific causal theory per se but it makes predictions: it doesn’t, by itself, give you time-stamped, domain-specific event predictions the way a physics or weather model does. What it does do—once you have some I on the table—is strongly constrain and often predict the kinds of wholes, categories, interactions, and failure modes that are possible or likely (e.g., if p= dog + cat + fish → then w=something in the neighborhood of ‘pets’).” It’s also more than “just grammar.” It makes strong, testable claims about what has to be present for any identity or theory to be coherent, and about the match between the way our mental models are organized and the way reality itself is organized.

Once you’ve gone through the DSRP-as-ontology paper, the calculus/Enclosure work, and the Science Summary in Camp, I’m happy to keep the conversation going. At this point, though, the most productive next move is to engage that ecology directly rather than for me to keep rephrasing slices of it in the comments. The belts are designed to build this understanding stepwise; you may find they make the ontology side much easier to see.

Message 9: Benjamin responds to Derek - 23/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek,

Thank you for pointing me to the paper and making it available. I’ve downloaded it and had a quick skim, and it already adds important context that I didn’t have from the PDFs I’d previously read.

I also want to say thank you for the exchange overall. The conversation has been genuinely productive, and I appreciate you taking the time to respond so thoughtfully and to share the relevant artifact.

I’m going to take some time to read the paper properly and reflect on the messages you’ve kindly shared.

An update to the post is coming in the next few days. This paper discusses scope, framing, and boundaries that are directly relevant to what I’m trying to write about, and I want to make sure I represent your claims accurately and engage them on their own terms - not as a strawman.

Thank you again,

Benjamin

Message 10: Benjamin responds to Derek - 26/12/2025 AEDT

Hi Derek Cabrera,

I hope you’re well.

Thank you again for taking the time to engage with my questions, and for releasing the “DSRP as Universal Ontology” page on 22 December. I’ve now read through all the materials you shared, including the ontology paper and the related ecology you pointed me to.

I’ve updated Part 3 of my series to reflect your framing more faithfully, and to focus specifically on the “handoffs” and boundary conditions that follow even if one grants the structural-ontology claim. I’d really appreciate your review for accuracy, especially where I quote or paraphrase your position, and for any corrections you think are needed.

Here’s the updated article:

https://www.benjamin-mosse.com/2025/12/15/universality-and-the-limits-of-dsrp-theory-part-3.html

If you’re willing, I’d also value any brief notes on where you think I’m still misunderstanding the claim, or where the wording could be tightened to match your terms.

Thanks again for the constructive exchange - I’ve found it genuinely clarifying.

Kindest Regards,

Benjamin

Message 11: Derek responds to Benjamin - 26/12/2025 AEDT

I appreciate the continued engagement and the effort to refine the framing. I think we’re now very close, so I want to focus on one narrow but decisive point.

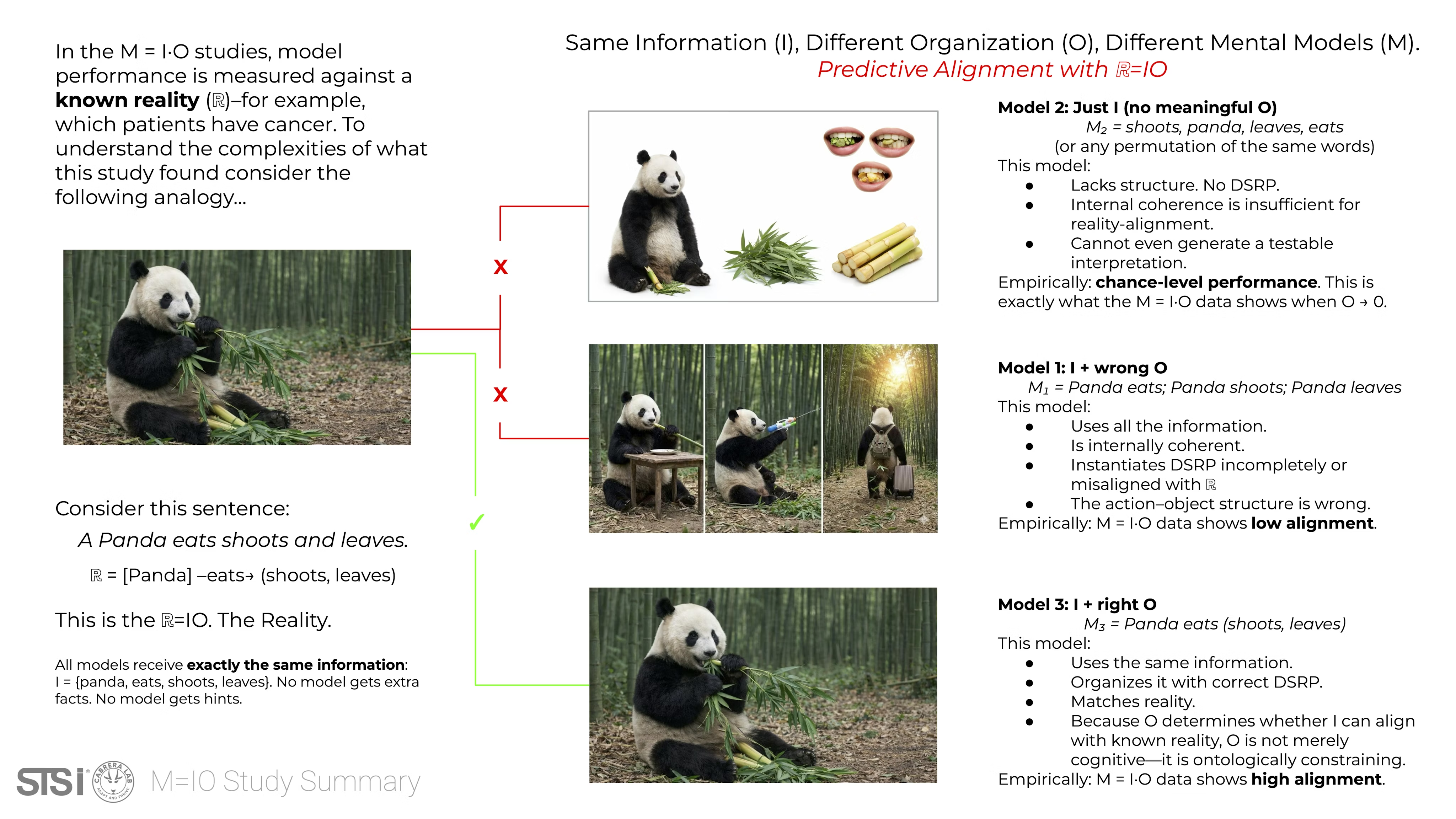

The core claim of DSRP as ontology does not hinge on whether it adjudicates between competing domain theories. It hinges on whether organizational structure is empirically implicated in model–reality alignment when reality (ℝ) is known.

That is exactly what the M = I·O results show.

Across controlled experiments on three datasets (biological, visual, and textual), holding information (I) constant and scoring models against known ℝ, differences in organization (O) systematically produced differences in alignment/fitness. Information alone did not rescue misalignment; correct organization did. This was not an additive effect but a robust multiplicative I×O interaction (p < .001). In short: organization is causally implicated in alignment, not merely in coherence.

DSRP does not replace domain science, nor does it make content irrelevant. It constrains what kinds of organized models can possibly align with reality at all. That is precisely what a structural ontology does. Logic, mathematics, and information theory operate the same way: they do not pick empirical winners, but they impose necessary constraints upstream of adjudication.

The panda slide below is a 1:1 structural analogy of the M = I·O experimental logic — not the actual data. It holds I constant, varies O, assumes a known ℝ, and shows how alignment changes. Its purpose is to make the empirical result legible, not to substitute for the studies themselves.

So yes — multiple coherent models can exist. But they do not align equally with ℝ, and organization is causally implicated in that difference. That empirical fact is the ontological hinge.

Happy to clarify further if useful.