Invisible but Real: Software as part of the Fabric of Reality

19 Nov 2025After reading my summary of Chapter 4 of The Fabric of Reality, my friend Michael challenged me to distil David Deutsch’s core mental model into something the public can understand - clear enough to be accessible, but not so simple that it becomes wrong.

This article answers that challenge. Using a familiar, everyday scenario, I will show why you should treat software as real - even though it is invisible, intangible, and usually described as virtual.

When Reality Requires Software

Suppose a major bank suffers a data breach.

That breach produces real, observable consequences:

- Sensitive data was stored and managed by digital systems

- Criminals accessed specific records inside those systems

- The stolen data was then used to commit identity fraud

- Victims were impersonated in real financial transactions

- The bank issued formal notifications and took operational action

These events require an explanation.

And any serious, high-level explanation that actually makes sense of them includes software.

The Explanation Requires Software

Let’s begin with the simplest explanatory claim:

2.1. A data breach is the unauthorized access to, or disclosure of, digital information.

2.2. Digital information is physically instantiated and transformed by hardware acting according to software.

2.3. Therefore, our best explanation of a data breach includes software.

Most people would accept this argument but the more powerful explanation of why software is real is still ahead.

The Explanation Must Be Specific

To explain the breach, we must provide exact answers to questions such as:

- What software was running?

- Which components or features were involved?

- What data did the software have access to?

- Which feature contained the flaw?

- What was the precise vulnerability?

- How was that vulnerability exploited?

Every detail must be accurate.

If you change the answer to any of these questions, the explanation stops working.

For example:

-

If the vulnerability does not exist in the software that was actually running, the breach cannot be explained.

-

If the software did not have access to the stolen data, it could not have been the mechanism by which the data was taken.

Change the key details, and the explanation fails.

This is what David Deutsch calls a hard-to-vary explanation: an account whose details cannot be altered without destroying its ability to explain the event.

Software is real not because it is physical, but because it plays an indispensable explanatory role in the causal structure of reality.

The Criteria for Reality

David Deutsch’s criteria for reality can be roughly summed up in three propositions:

- The ‘entity’ or the ‘part’ has explanatory reach: it explains many different phenomena.

- Its removal breaks our best explanations: without it, the explanations collapse.

- No rival explanation works better: alternatives are worse or impossible.

Using Systems Thinking

To try and make Deutsch’s criteria for reality even clearer, let’s apply the basic moves from DSRP Systems Thinking.

The Fundamental Distinction

Popperian epistemology distinguishes between better and worse theories.

Better theories are those that solve more problems, make riskier (more easily falsifiable) predictions, and survive more severe criticism.

The key idea is that we should prefer, at any given time, the theories that have better withstood criticism, using general criteria such as falsifiability, explanatory power, problem-solving capacity, and simplicity – not any claim that a theory has been finally “proved” or is the best forever.

Defining “Better Explanation”

Here’s an IS / IS NOT Table for defining what a better explanation generally looks like:

| Better explanation IS | Better explanation IS NOT |

|---|---|

| Explanatory | Merely descriptive |

| High-reach | Narrow |

| Hard-to-vary | Easy-to-vary |

| Unified | Fragmented |

| Deep | Superficial |

| Testable-in-principle | Untestable even in principle |

| Precise | Vague |

Epistemological Stance

Alongside what counts as a better explanation, we also need the right epistemological stance - how we treat theories and knowledge.

| Popperian+Deutsch stance IS | Popperian+Deutsch stance IS NOT |

|---|---|

| Critical | Authority-based |

| Conjectural | Inductive method |

| Fallibilist | Proof-based certainty |

| Non-justificationist | Justificationism |

| Non-inductive | Empiricist foundationalism |

| Explanatory-focused | Prediction-only |

| Realist | Instrumentalism / “useful fiction” |

| Error-correcting | Consensus-based |

| Open-ended | Final truth |

| Problem-driven | Data-first foundationalism |

Together, the quality of our explanations and this epistemological stance define the system by which we create new knowledge and decide which entities we should regard as real.

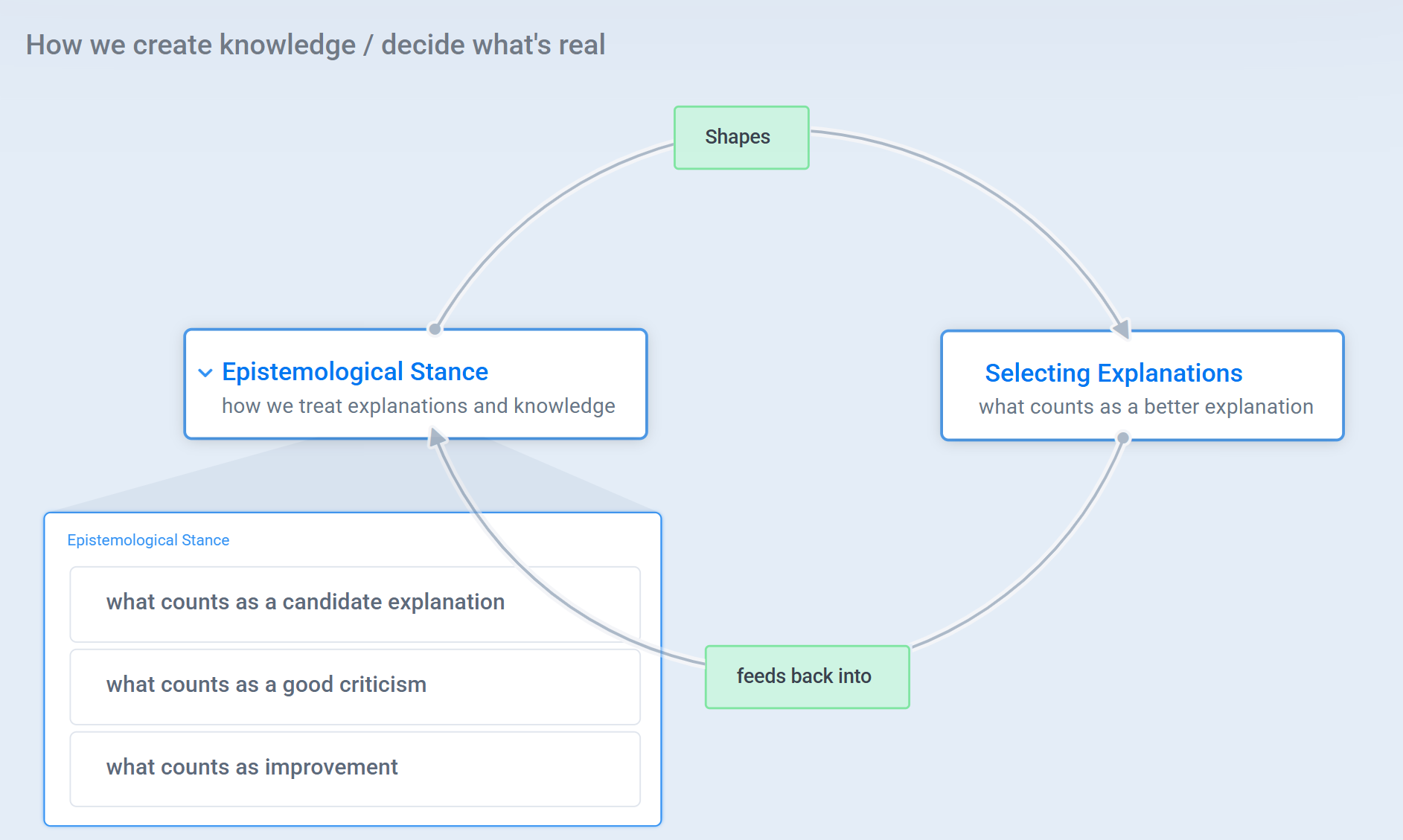

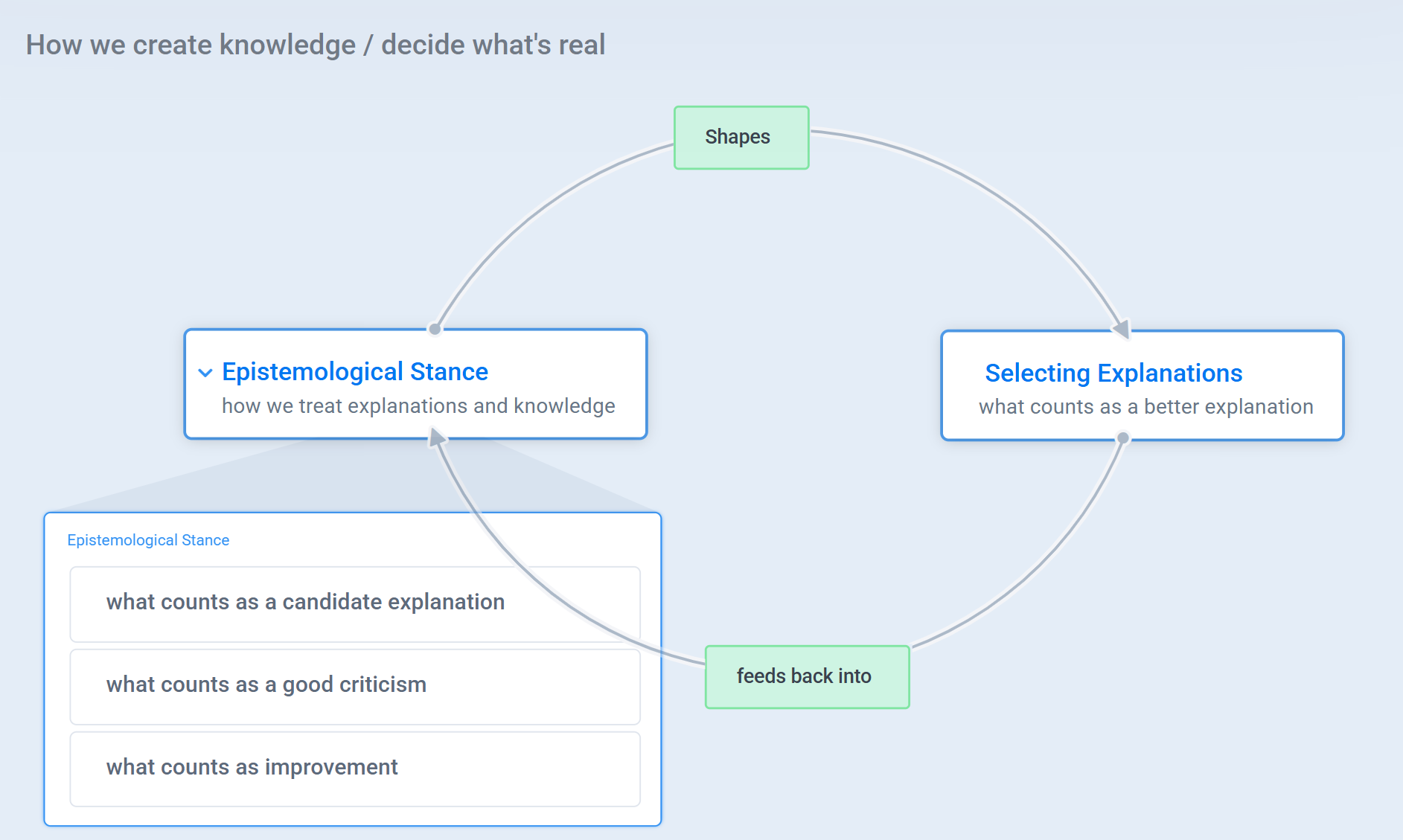

The Systems Map

Here’s a Systems Map that explains the relationship between the epistemological stance and selecting explanations:

The Popperian system looks more closely to this:

Conclusion

We started with a simple question: if software is invisible and usually called “virtual”, why should we treat it as real?

By examining a concrete case - a bank’s data breach - we saw that any serious, high-level explanation of what happened includes software.

Not as a metaphor, but as a precise, hard-to-vary part of the story: which software ran where, with access to which data, with which flaw, exploited in which way. Change those key details, and that explanation fails.

Using David Deutsch’s criteria for reality, and a Popperian+Deutsch stance on knowledge, we can say: software counts as real because it has explanatory reach, because removing it breaks our best explanations, and because no known rival explanation works better.

In that sense, software belongs in the same class as electrons, genes, and wave functions: entities we treat as real because they are indispensable to the way our best explanations describe how reality behaves.

And with that, I hope I’ve finally answered Michael’s request - and possibly made it a bit harder for you to ever call software “just virtual” again.

Thank you for reading. If any errors or misunderstandings appear in this article, they are entirely my own and should not be attributed to David Deutsch or his work.