A Practical Guide to Popper's Epistemology (via David Deutsch)

03 Nov 2025Where does knowledge come from? How do we decide that one explanation is better than another? These are foundational questions across every field of human inquiry.

In The Fabric of Reality (TFoR), David Deutsch presents a powerful defense of Popperian epistemology — the view that knowledge grows through bold conjectures and the systematic elimination of errors. Deutsch argues that this framework is one of humanity’s four most fundamental explanatory theories, alongside quantum physics, evolution by natural selection, and the theory of computation.

In this article, I will outline what I understand Popperian epistemology to assert.

The Four Parts of Popperian Epistemology

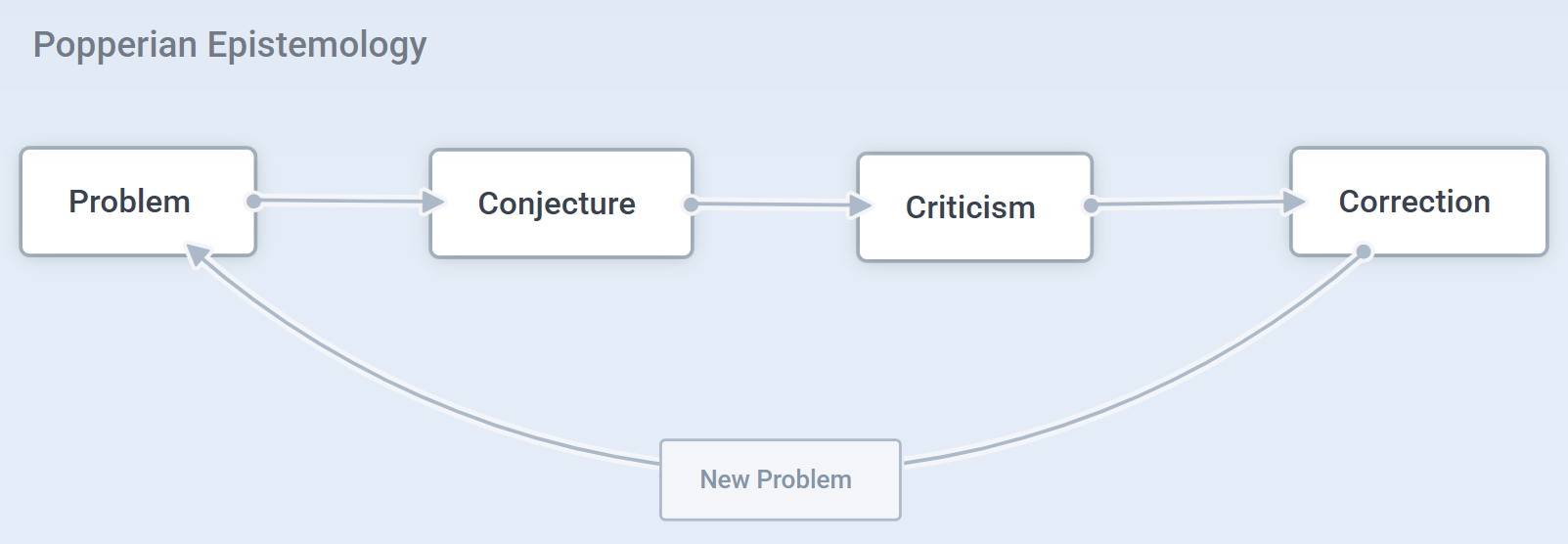

Karl Popper held that knowledge grows through a continuous process of problem solving:

We begin with a problem. In Popper’s sense, a problem can arise from many sources. It may come from conflicting observations, from a theory that fails to explain something, or simply from a goal we have not yet achieved.

To address the problem, we create a conjecture. A conjecture is a tentative explanatory theory that attempts to solve the problem. Sometimes we invent new conjectures. Other times we compare existing ones to see which one offers the best explanation.

We then apply criticism. Criticism includes attempts to find errors in the conjecture, to refute it, or to identify weaknesses. Criticism may lead to minor improvements or to the conclusion that the conjecture is false or inadequate.

If the conjecture survives criticism, we correct and refine it based on what the criticism has revealed. The theory remains tentative, because it is always open to further improvement or refutation.

Even after we’ve refined a theory, or learned something new, further problems arise. Each problem leads to new conjectures and new criticism. Knowledge therefore advances through this cycle of conjecture, criticism, and improvement, not through justification or attempted verification.

How should we select between available theories?

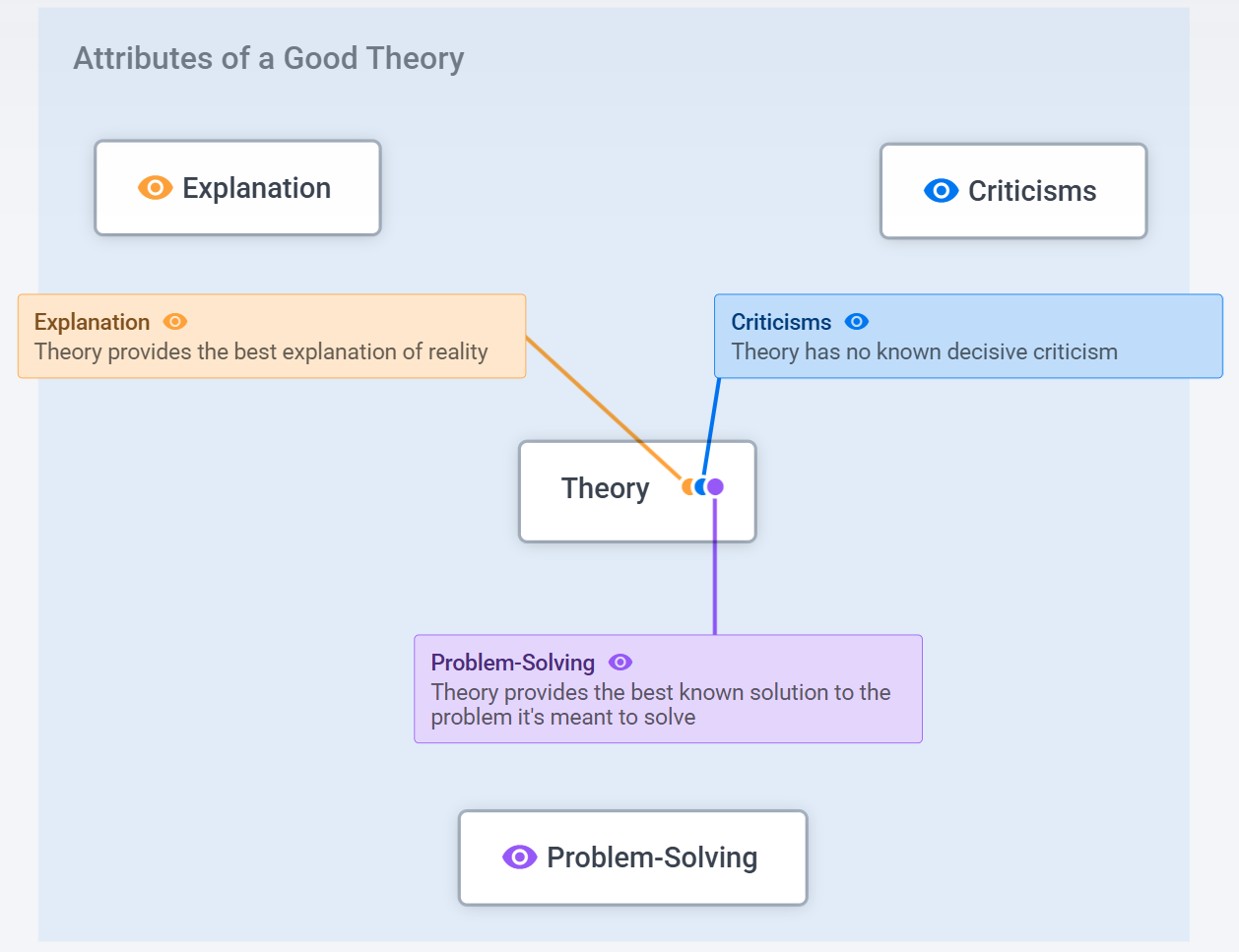

Popper’s epistemology holds that we can assess a theory’s quality by how well it withstands criticism and solves problems, not by attempts to justify or prove it. Three key considerations guide how we assess whether a theory is currently the best available among alternatives:

-

Explanatory power: The theory should provide the deepest and broadest explanation of the phenomena it addresses.

-

Problem-solving capacity: It should solve more problems, and solve them better, than rival theories.

-

Survival of criticism: The theory has withstood all known criticisms so far, and attempted refutations should have led to its improvement.

According to Deutsch, the most fundamental theories we currently possess satisfy these criteria to an extraordinary degree. His project in The Fabric of Reality is to present and unify these leading theories.

Popperian epistemology does not prove or justify theories. It only explains why some theories are better than others at a given time, and remains open to further improvement.

Deutsch’s Mental Model for Criticizing Theories

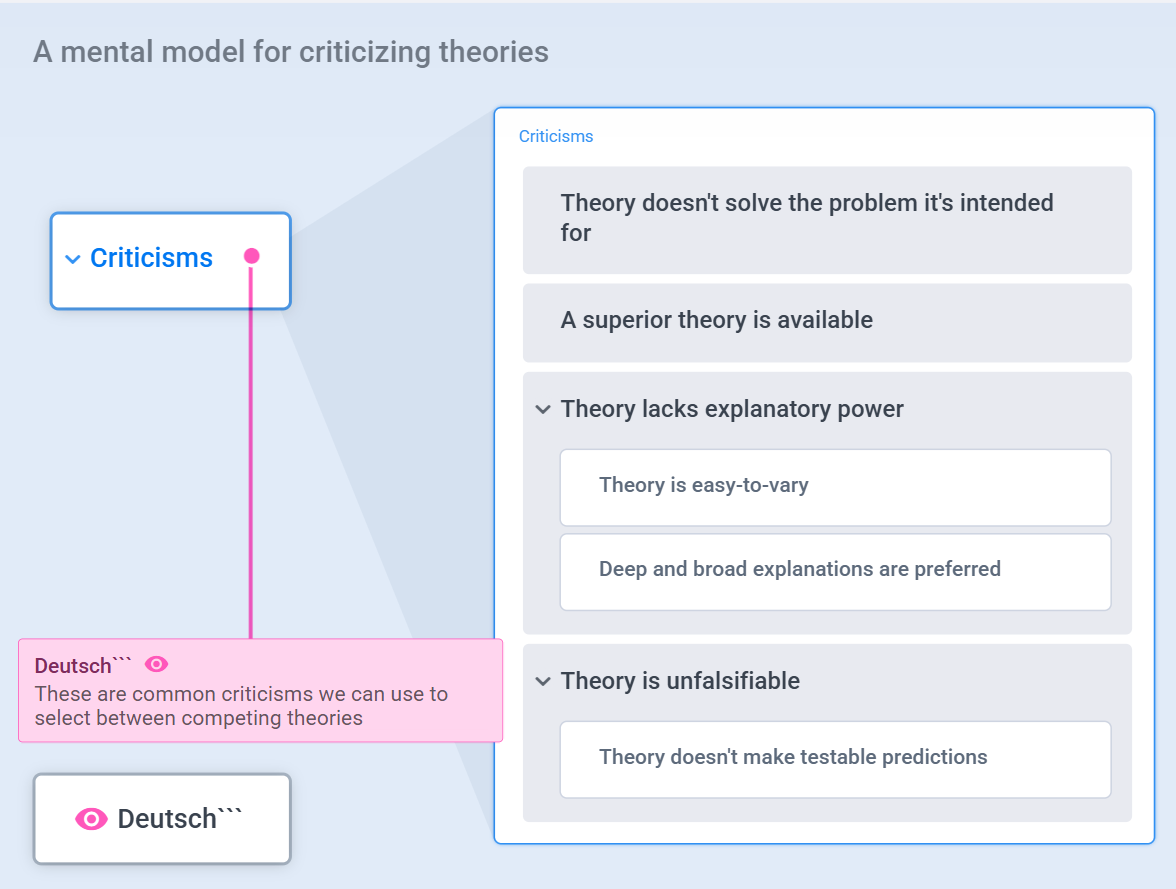

From Popperian epistemology, we can derive a simple and powerful set of principles for evaluating and criticizing theories:

-

Failure to solve the problem: If a theory does not solve the problem it was proposed to solve, it has been refuted for that problem.

-

Prefer the better explanation: If a rival theory offers a deeper, broader, and more error-correcting explanation, that rival theory should be preferred.

-

Improve shallow explanations: If a theory lacks depth or reach in its explanation, it should be improved or replaced by a more explanatory one.

-

Critique easy-to-vary theories: If a theory is easy to vary without losing apparent fit to observations, this indicates weak explanatory power.

-

Reject unfalsifiable claims in science: If a claim is constructed to be unfalsifiable, it does not belong to scientific inquiry and cannot compete as a scientific explanation.

Evolutionary Epistemology

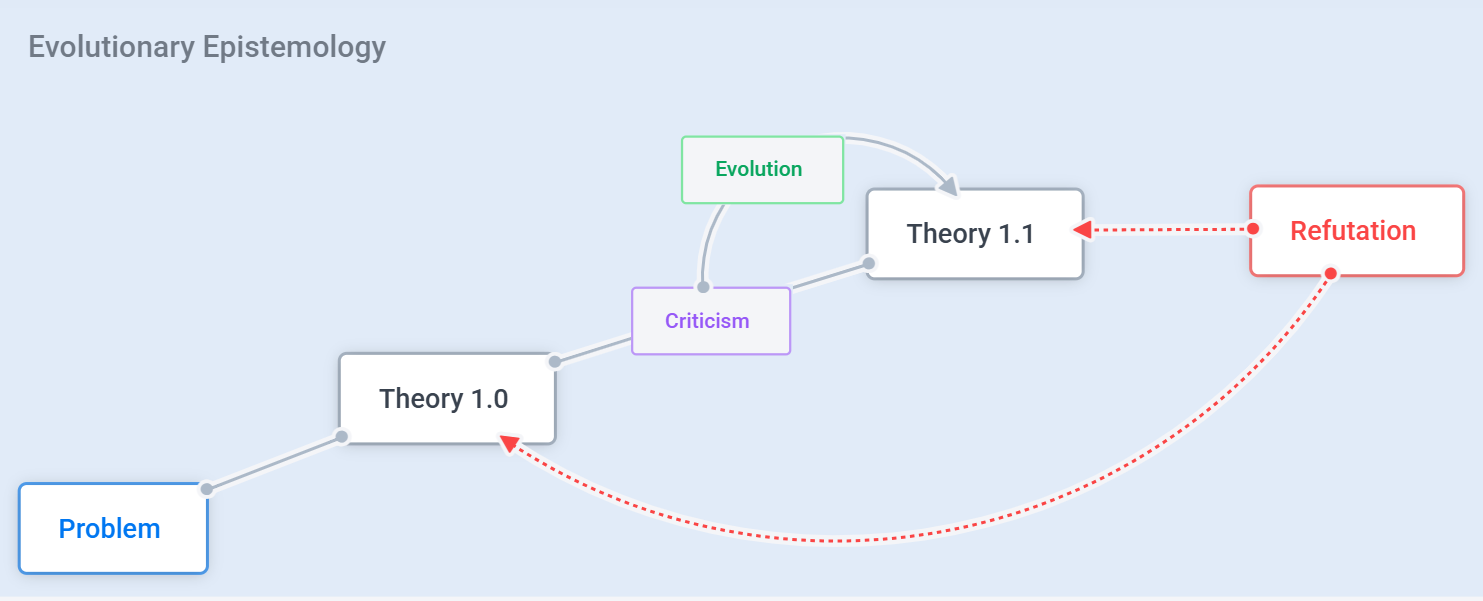

Popper’s epistemology can be described as evolutionary because it shares key structural features with evolution by natural selection.

Ideas play a role analogous to organisms: they vary, they face selective pressure through criticism, and only the most error-resistant survive. Through this process of conjecture and criticism, theories are either improved or eliminated.

The image below illustrates this concept:

Final Word

The following reflects my own view, not necessarily that of Popper or Deutsch.

There is no shortage of bad theories in the world. The internet has amplified this problem. With platforms like YouTube enabling anyone to broadcast ideas and profit from attention, we are surrounded by claims and explanations that have already been refuted, or that are so undeveloped they have never faced any serious criticism - sometimes nothing more than one person’s untested idea.

My advice, to myself and to others, is to prioritize learning and using theories that have been rigorously criticized, that solve real problems, and that offer deep explanatory power. In my experience, ideas that have survived extensive attempts at refutation provide far more leverage in thinking and decision-making than fashionable or untested claims.

In practice, a good theory is one of the most powerful tools you can have.