Refuting Cyber Skills Frameworks

23 Oct 2025This week, I took part in a roundtable discussion hosted by Home Affairs on uplifting the cyber workforce.

One idea that came up several times was that the industry could benefit from a clear Cyber Skills Framework that employers, universities, TAFEs, graduates, and professionals could all align on.

-

Employers: Help education institutions understand the specific skills you need graduates to have.

-

Education Institutions: Align degrees and courses more closely with employer requirements.

-

Students: Gain clarity on what employers value and build the right skills.

-

Employees: Identify the skills you are missing to advance your career.

In theory, it seems like a common-sense idea.

But Cyber Skills Frameworks already exist and are widely available, so why haven’t they solved the problem of aligning all the agents in the system?

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of Cyber Skills Framework:

- ASD Cyber Skills Framework

- CIISec Skills Framework

- DoD 8140

- European Cybersecurity Skills Framework

- NIST NICE Framework

- OpenSSF Cybersecurity Skills Framework

- Queensland Government cyber skills framework

- SFIA

- Saudi Cybersecurity Workforce Framework

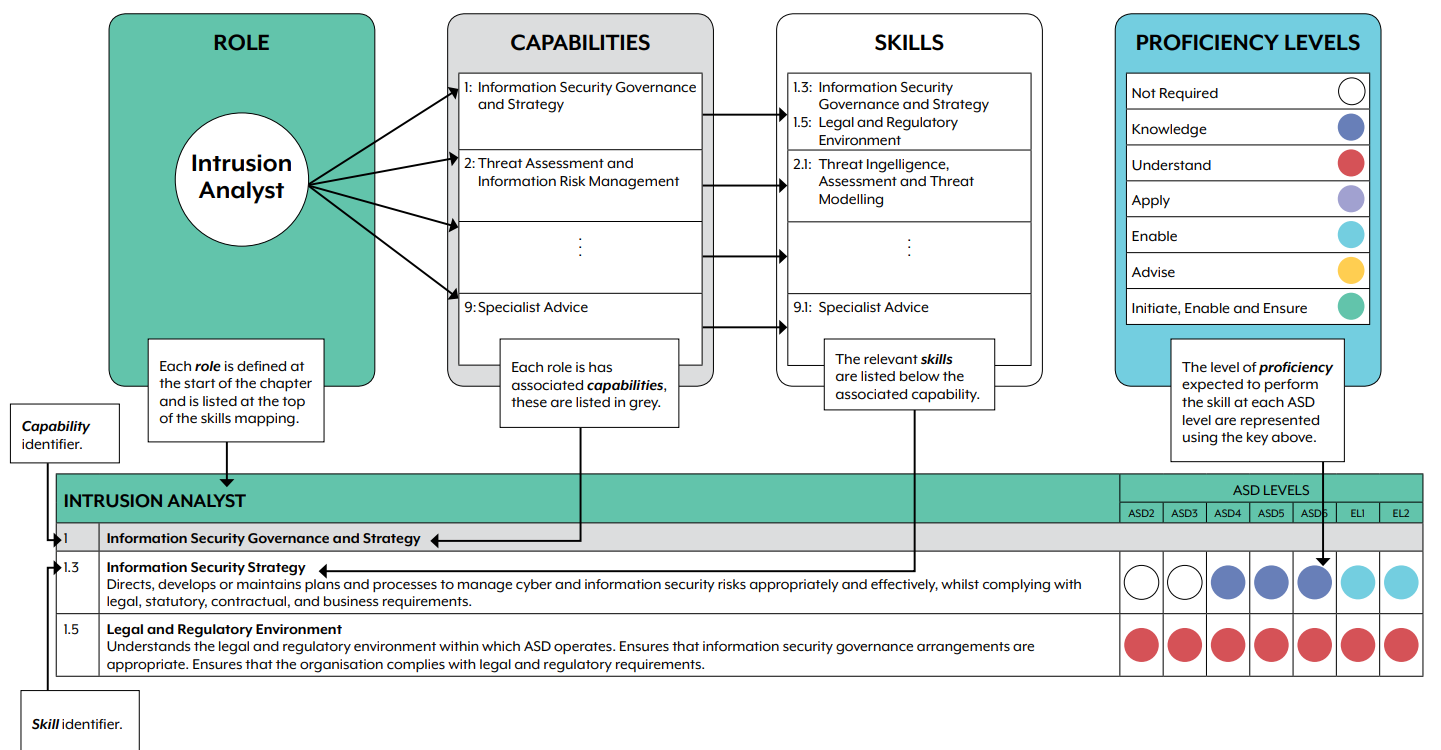

Take my preferred example, the ASD Cyber Skills Framework. It is already mapped to both the CIISec Skills Framework and SFIA.

It contains clear, well-structured tables that set out expectations that could easily be adapted for the private sector.

Let’s look at one of its requirements for a Cyber Threat Analyst:

“Monitors network and system activity to identify potential intrusion or other anomalous behaviour. Analyses the information and initiates an appropriate response, escalating as necessary. Uses security analytics, including the outputs from intelligence analysis, predictive research and root cause analysis in order to search for and detect potential breaches or identify recognised indicators and warnings.”

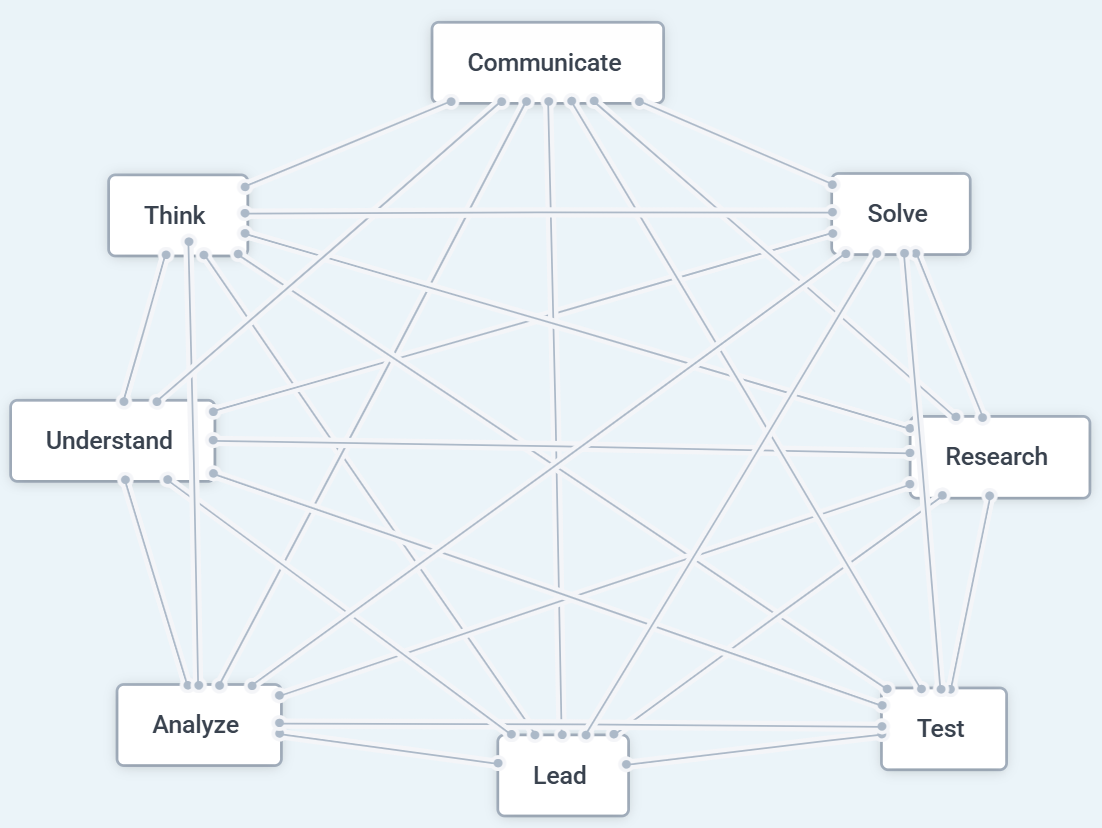

The key challenge for educational institutions is that, whether it’s this requirement or another, cyber skills are not linear, mechanistic, or neatly ordered. There’s no step-by-step and universal method for “identifying potential intrusions” for example.

Instead, cybersecurity is dynamic, filled with uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

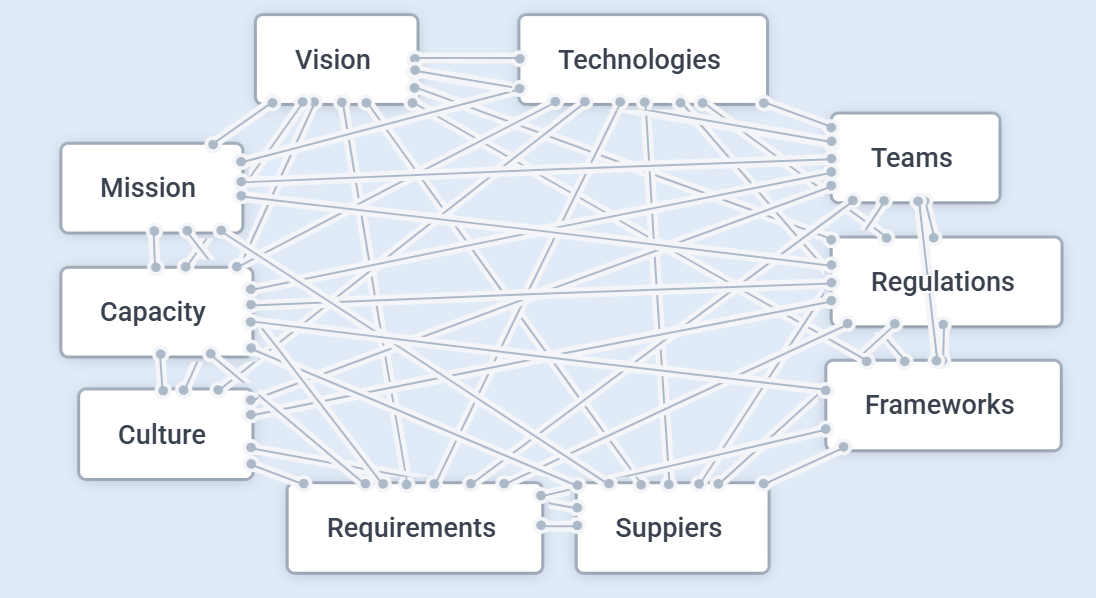

So in reality, cyber skills look more like this:

You’re given a problem, and you’re expected to draw on a wide range of skills and apply them in a multivalent way to solve it.

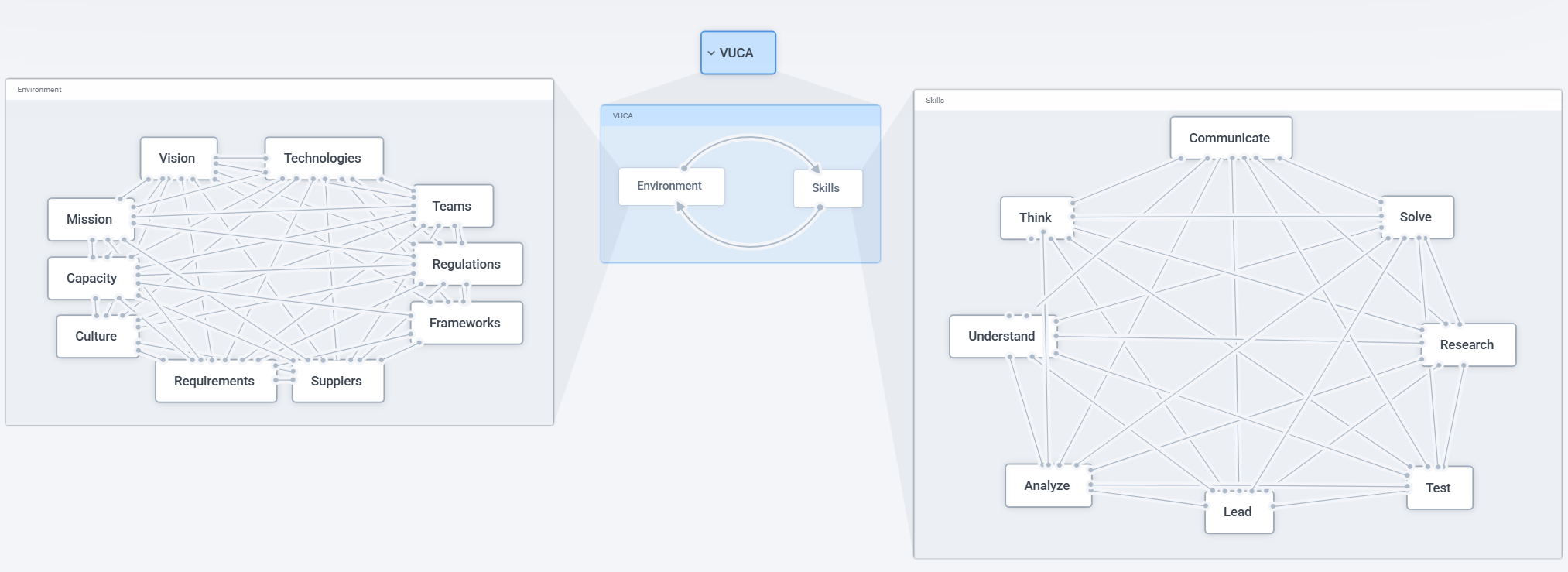

And of course, the environment within which cyber professionals is also volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA):

So when we say we are looking for a Cyber Threat Analyst, we are really looking for someone who can operate within a system that looks like this while performing tasks such as “monitoring the network to identify anomalies”.

Once this is understood, it becomes clear why existing Cyber Skills Frameworks have failed to improve people’s skills or help graduates find employment:

-

Theoretical courses and exams alone do not develop real problem-solving ability

-

Degrees in which students spend fewer than 200 hours on practical, hands-on work leave graduates unprepared for real-world challenges

-

Cyber ranges built on pre-scripted environments fail to capture the complexity and ambiguity of real-world systems

-

Certificates alone do not give employers meaningful insight into the types of problems a candidate is capable of solving

-

Students who learn to game the education system by spotting patterns, filing complaints, or expecting to be given answers - behaviors that work within the current system - often carry those same expectations into the real world, where they no longer apply

Creating yet another framework in the hope that it will succeed where others have not is a futile endeavour.

Fundamentally, Cyber Skills Frameworks are simply someone else’s perspective on what a cyber professional should look like. That’s why there are so many frameworks rather than a single one.

More often than not, that perspective does not reflect the reality of an organization’s specific environment and the skills required to succeed within it.

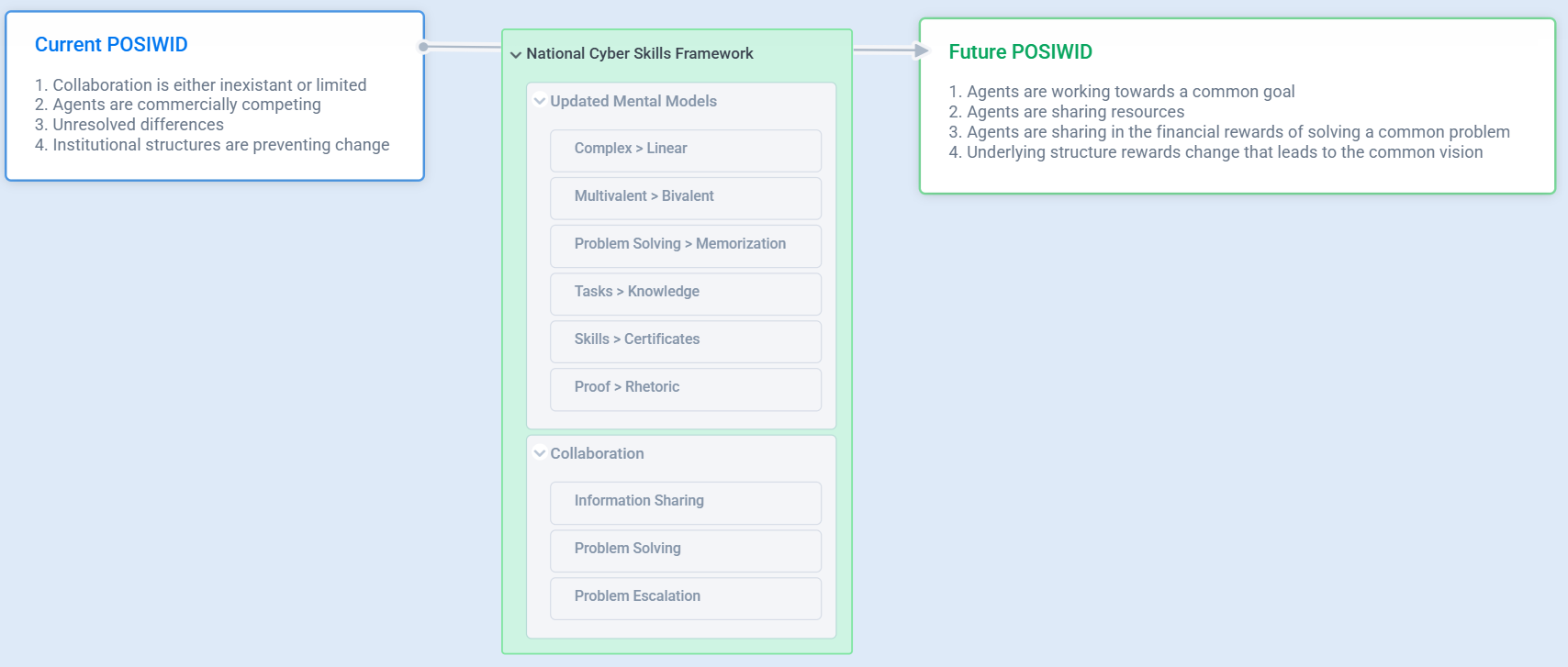

The real value that a Australian Cyber Skills Framework might deliver is improving the relationship between the agents in the system and create a culture change:

If Australia decides to develop its own Cyber Skills Framework, the initiative should be viewed as an opportunity to update the mental models of all agents within the system, rather than an attempt to create a better taxonomy or uncover something that existing frameworks have somehow missed.

The most effective path forward would be to build on an existing framework, make targeted adjustments where necessary, and focus our collective effort on reshaping how employers, educators, and professionals think about cyber skills, rather than reinventing the framework itself.

The new mental models are already known — the challenge is that too few participants within the system have truly integrated them.

- VUCA over LAMO

- Multivalent over Bivalent

- Problem Solving over Memorization

- Tasks over Knowledge

- Skills over Certificates

- Proof over Rhetoric

If Home Affairs were to fund or endorse a Cyber Skills Framework without prioritizing a targeted culture change initiative, there is a real risk of achieving the opposite effect. The status quo could become further entrenched, with those who already benefit most from the current system using the new framework to consolidate their position.