Why Cyber Education in Australia is F*cked

08 Oct 2025Everyone says Australia’s cybersecurity education system is broken. It isn’t — it’s doing exactly what it was built to do.

It absorbs public money, recycles empty promises of “shortages,” and rewards those who protect the illusion, not those who produce talent. I’ve spent a decade inside this system - meeting with universities, TAFEs, and government-funded organizations - and have watched ideas that could have lifted national capability disappear into bureaucracy or self-interest.

The Real is that this isn’t failure; it’s function. The system was never designed to create world-class practitioners. It was designed to sustain itself.

On October 10th, 2025, a post by Matthew A. caught my attention on LinkedIn. In it, Matthew shared how he’d been told - by countless people and organizations - that there was a massive cybersecurity skills shortage in Australia. Motivated by that message, he went all in, enrolled in a Diploma of Cyber Security, worked hard, and yet still found it impossible to land a job.

I don’t blame Matthew. He did everything the system told him to do. The failure is not his - it’s the industry, the education sector and the government. It’s a structure that keeps repeating the same story about skills shortages while producing education that doesn’t translate into employable skills.

I’ve been working to change that since 2015. And I want to build on Matthew’s message by laying out what I’ve seen firsthand, with evidence to back my claims. My goal to expose the underlying issues that keep Australia from having world-class cybersecurity education.

This story starts in 2015, when I hired an external consultant to help design an Advanced Diploma in Cyber Security Operations. Through that process, I was introduced to some of the people developing what would become the Certificate IV in Cyber Security.

Even without seeing the full draft of the Cert IV, it became obvious early on that the course would be outdated the moment it launched. And that’s when I decided not to engage in further discussions with that group and instead chose to continue pursuing my own path.

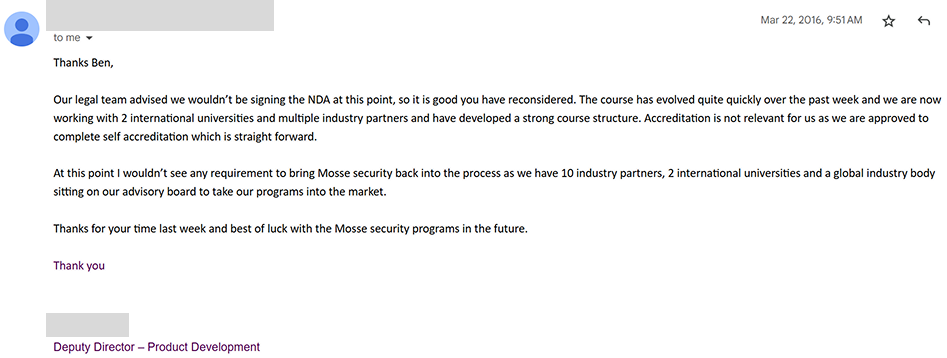

In 2016, we met with two major Australian universities and one TAFE. It didn’t take long to realize they had no real interest in a genuine partnership. What they wanted was access to our training materials and for us to teach without compensation - simply so they could say we were working with them.

Here’s an email I received from one of them after I declined to move forward with that proposal:

Then, in April 2017. The government announced the creation of an well-known organization who’s mission was to grow the national cybersecurity industry.

I flew to Sydney for their launch event. In my briefcase was a printed copy of our Advanced Diploma in Cyber Security Operations - a model we had worked hard to design and believed could meaningfully lift the standard of education in the country. I handed it to them in good faith, under the promise of a follow-up meeting to discuss how they might support or collaborate on the initiative.

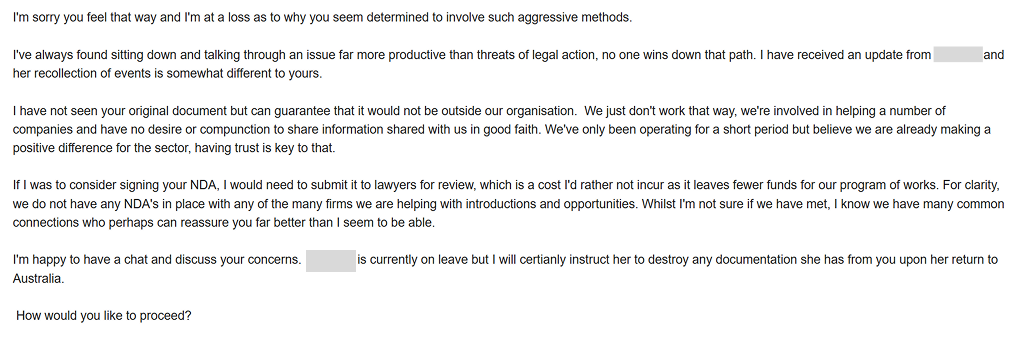

By June, after several emails and phone messages, I still hadn’t heard a word. The silence was unsettling. Since the materials contained confidential intellectual property, I asked our lawyers to formally request that the documents be returned and that both parties sign a mutual NDA.

That finally got a response. They informed us that they did not sign NDAs with any of the companies they were engaging with - even while collecting and reviewing their intellectual property:

After a few email exchanges, the matter was resolved. I finally met with them on June 30th, 2017, and unfortunately learned that to receive their help, I would need to owe an open favour to a certain individual in the future:

“We’re not a fee thing, like we don’t charge you any money. I always describe it to people going: look the only thing that happens is you owe me a favour. Right, that’s how the world goes around. And at some point I’ll tap you on the shoulder and want to cash that in. Now the people who know me really well get a little bit frightened by that.”

That was not a condition I was willing to accept, and I decided not to proceed with the arrangement.

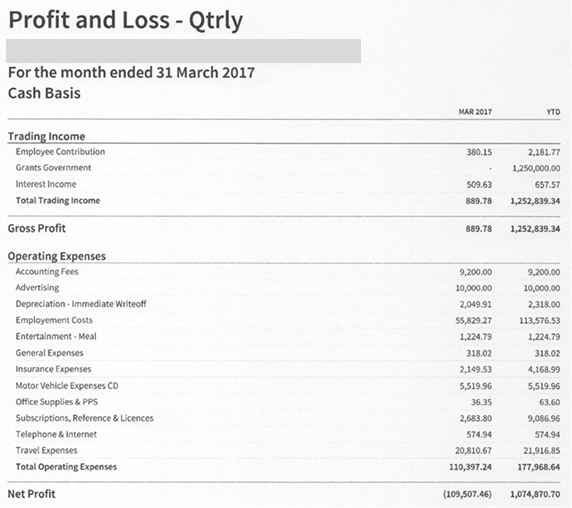

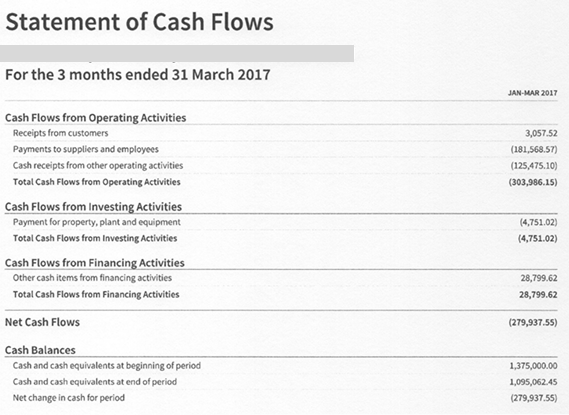

Furthermore, the same individual accidentally emailed me part of the organization’s financial records. That’s when I discovered that money was being spent like wildfire, yet I couldn’t find a single line item showing funds directed toward a project that genuinely supported the Australian cybersecurity ecosystem at the time.

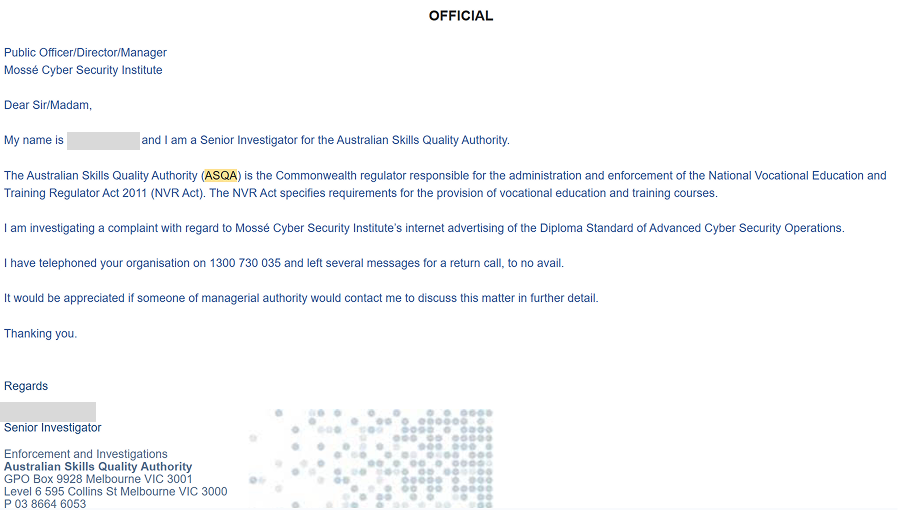

Fast forward to 2020. I made the decision to open-source our Advanced Diploma of Cyber Security Operations. Shortly after, an education provider took notice and filed a complaint with the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA), the national regulator.

An investigator reached out, and after a few legal exchanges, we agreed to rename it “an open-source curriculum for a degree qualification.” The issue, it turned out, wasn’t the content — they simply objected to our use of the word “diploma.”

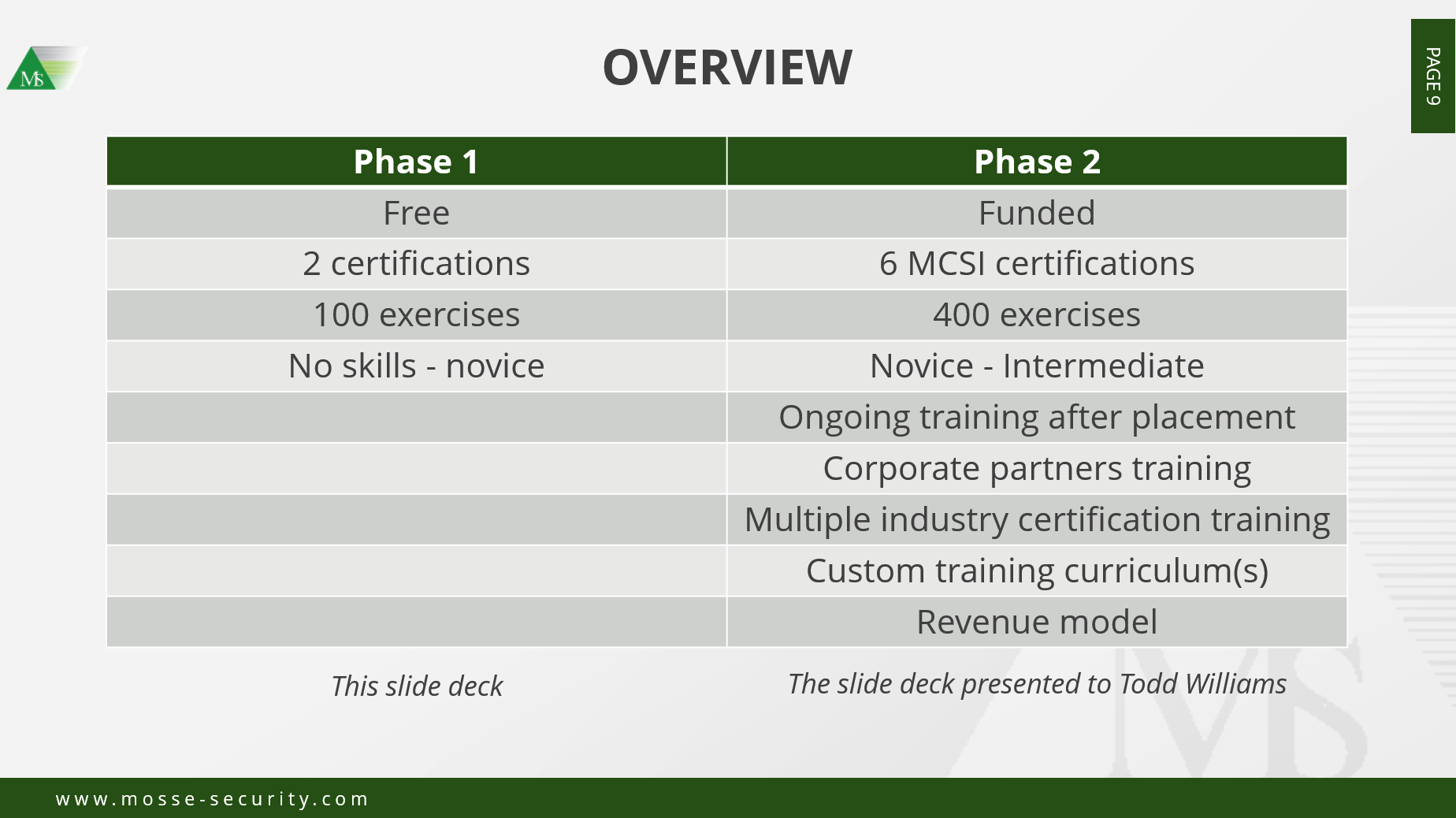

That same year, we submitted an unsolicited proposal back to that not-for-profit organization, which by then had undergone a change in leadership. We offered to deliver a nationwide program capable of training an unlimited number of students across Australia, and to share the revenue with them to help the organization transition away from government funding.

The proposal gained traction with the NSW and SA nodes, but when it reached higher levels for approval, it ultimately stalled.

These experiences, along with a few others, gradually made me lose interest in collaborating with the broader education ecosystem. We still receive inquiries from universities, TAFEs, and other organizations, but they rarely lead anywhere. Our level of engagement today is minimal.

It doesn’t seem to matter that MCSI has become one of the largest cybersecurity institutes in the world - with over 40,000 students across 80 countries, and a proven track record of helping students land jobs through a portfolio-based approach.

They have their model, and we have ours. As long as people continue to believe that a university degree or TAFE certificate is the key to employment — or a pathway to a visa — those institutions will keep doing what they’ve always done.

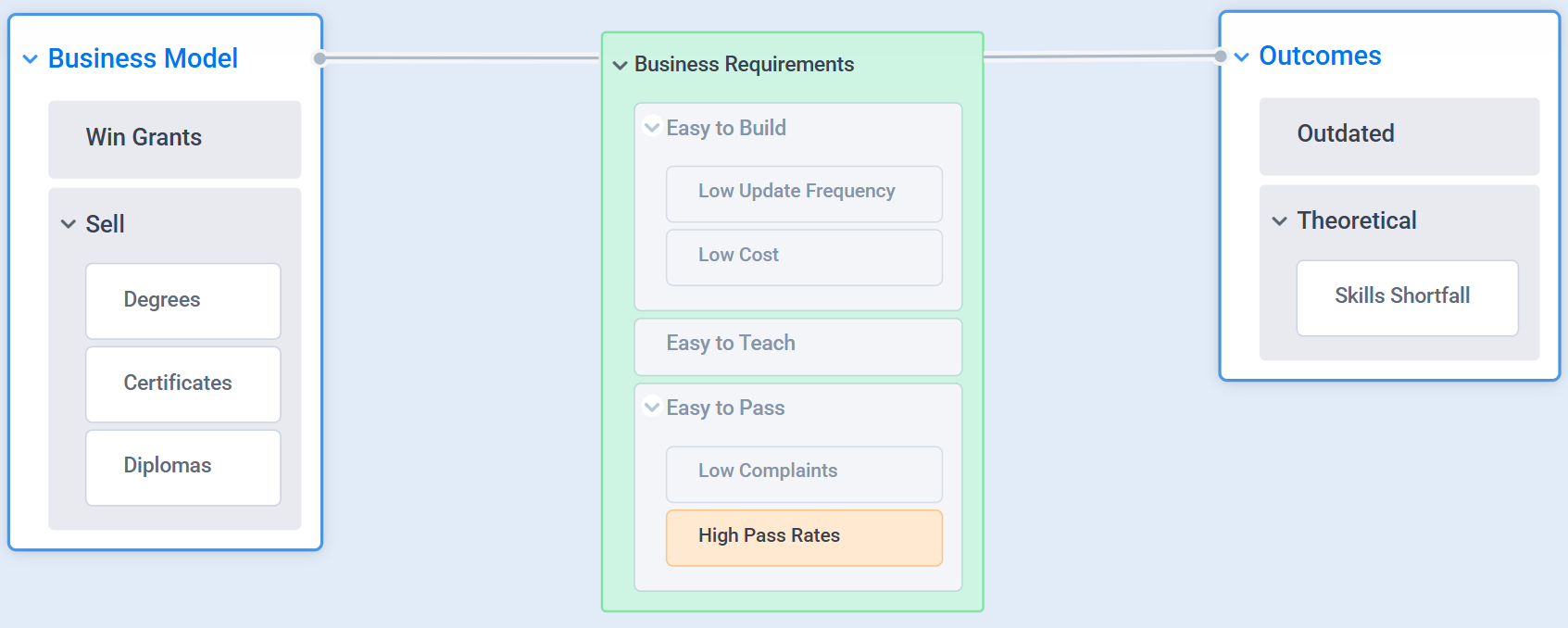

The purpose of a system is what it does. Their system is designed to maximize revenue within the Australian ecosystem, not to produce the most capable cybersecurity professionals employers are looking for.

The good news is that cybersecurity itself is an unstoppable, infinite game. You don’t need a degree, a certification, an employer, or permission to play.

If you want to stand out, start doing cybersecurity in public. Publish one CVE a week. Threat model an app. Reverse engineer malware and share your findings. Use your OSINT skills to support investigative journalism. The list of legal, valuable, and creative contributions you can make is endless.

Matthew, what your degree didn’t give you wasn’t employment - it was the unstoppable hacker mindset. And that, once you build it, can help you break into anything.

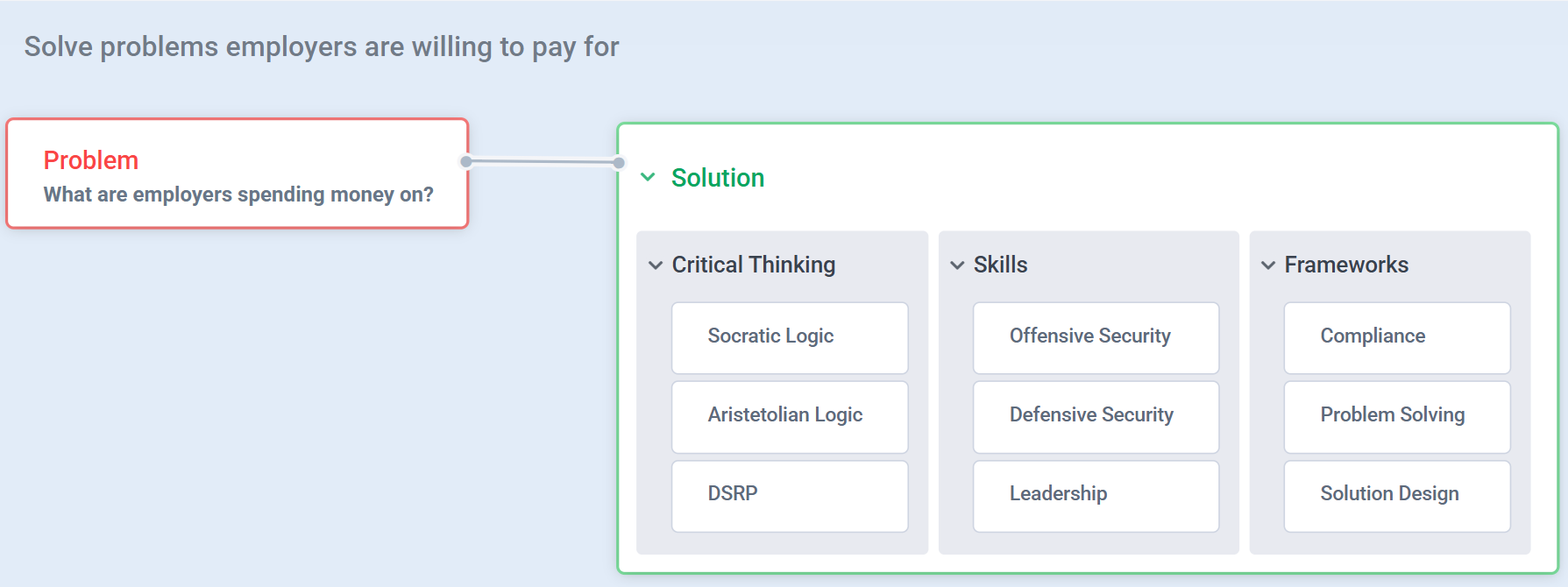

Whether you want a job in cybersecurity or to build your own business, your success depends on one question: what problems are employers willing to pay you to solve and can you prove to them you’ve got the skills to do it?