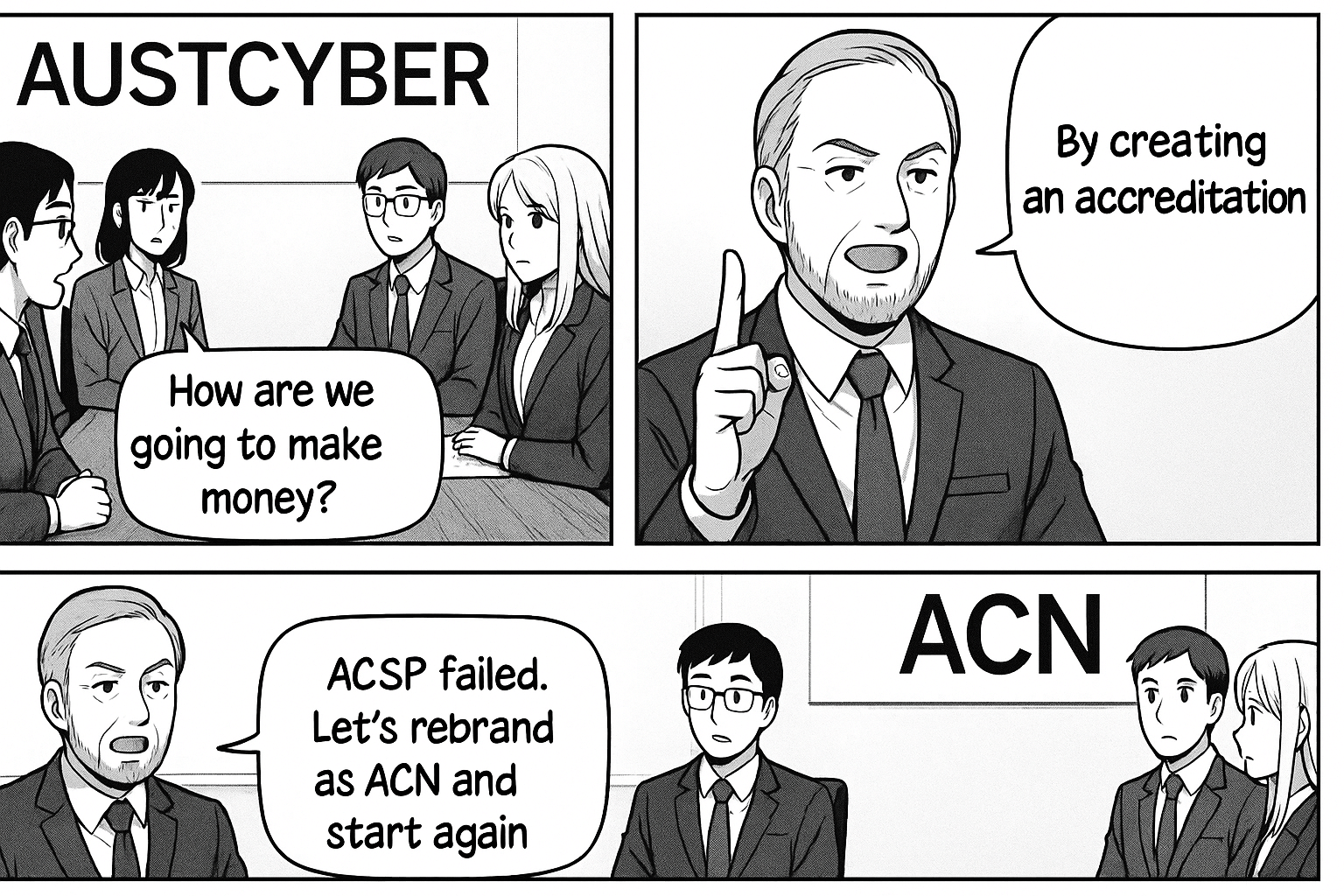

AustCyber Took Government Money to Professionalise Cyber. It Delivered Nothing.

26 May 2025AustCyber promised to professionalise cybersecurity, took public money, and delivered nothing. Now, the same actors return under a new banner, asking for more. This essay exposes the disavowed failure, the absence of accountability, and the quiet repackaging of a still-unproven idea.

In February 2021, Stone & Chalk acquired AustCyber, a government-funded Industry Growth Centre. Six months later, CEO Michelle Price resigned. Jason Murrell replaced her as Group Executive in September 2022 and remained until August 2023.

One month into Murrell’s tenure, Damien Manuel, then chair of the Australian Information Security Association (AISA), was invited to join a select group developing a national accreditation scheme to professionalise the cybersecurity industry. He was asked to sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement — barring him from discussing the process with the very members he represented.

It wasn’t until May 2023, that AustCyber publicly unveiled what had been kept quiet: the Australian Cyber Security Professionalisation (ACSP) program:

Led by AustCyber, the ACSP program aims to professionalise the fragmented cyber security industry in Australia, establishing global standards and enhancing trust in Australian cyber security professionals.

AustCyber released a video alongside its announcement, showing ten individuals meeting to “co-design” a professional accreditation on behalf of the entire industry — as if no one would object to such a top-down, closed-door process.

Tony Vizza, one of the creators of the ACSP program, said:

This is the first time all major industry players have come together to get an actionable plan in place for Australia’s growing cyber security industry

Two months later, AISA withdrew from the ACSP program. Damien Manuel later explained the decision: the scheme couldn’t function without passing costs onto professionals or relying on vendor sponsorship - a setup rife with conflicts of interest. This, along with a decade of AISA’s own research into the risks of professionalisation, made continued involvement untenable.

But the real questions remain: who funded the creation of the ACSP — and what was actually delivered?

Using the Wayback Machine, I recovered archived pages from AustCyber’s former website confirming that the Australian government funded and backed the ACSP:

I couldn’t determine whether the government provided new funding for the ACSP or whether AustCyber used what remained of its existing budget - though there exist a potential, but unconfirmed, Contract Notice candidate. But that detail no longer matters. What’s clear - and what AustCyber stated openly - is that the ACSP was funded by the government, and carried its support. That’s the fact we’re left with.

AustCyber continued to reference the ACSP in several public documents throughout 2023, including its submission to the 2023–2030 Cyber Security Strategy. But no concrete details were ever made public. For all intents and purposes, taxpayer money funded the initiative - and nothing tangible was shown in return. Cyber professionals are left asking the only question that matters: what was created, and what was told to the government?

AustCyber officially shut down on November 21, 2024. In its place, Jason Murrell, Jill Slay, Linda Cavanagh, Miranda Mears, Kathleen Moorby, and others launched the Australian Cyber Network (ACN), a new entity claiming to represent the industry.

It is now competing for a $1.9 million government grant to professionalise the cybersecurity workforce led by Ashley Bell at Home Affairs - the very goal AustCyber failed to deliver with the ACSP.

The question is no longer rhetorical. After a year of public funding, no public outcomes, and no transparency, what have Jason, Kathleen, and Jill, who spearheaded ACSP, done to earn a second chance at professionalising the industry?

If ACN is awarded another chance, and the defence becomes “we’ve learned from failure,” then the burden is clear: show the learning, show the repair, show how you addressed the risks raised by AISA and others.

The AustCyber story reveals what happens when process is mistaken for progress. Statements are issued, videos produced, consensus declared - yet nothing of substance is delivered. The failure is obvious, but disavowed: “We know we failed but let’s carry on like nothing happened.” That’s when good intentions start to resemble publicly funded careerism - and the spectre of that same failure now hangs over the new Home Affairs grant.

If professionalisation were truly a grassroots effort - endorsed by most cybersecurity professionals, backed by clear evidence, free from conflicts of interest, and driven by a shared, urgent problem - then this article wouldn’t need to exist.

If it weren’t funded with public money, or positioned as a solution without first addressing long-standing, well-documented risks, I would have nothing to contest. But that’s not the situation we’re in. This is a government-backed, government-funded initiative - launched without consensus, clarity, transparency, or accountability. In such a case, scrutiny is not hostility or a personal attack. It is responsibility.

Curious to know how Jason Murrell, Tony Vizza, and Tom Finnigan defend professionalisation? Watch their case on YouTube.

Important Clarification:

This essay focuses specifically on the ACSP and the new professionalisation grant by Home Affairs - not other initiatives led by AustCyber.

My intention is to speak a simple truth: there was an attempt to professionalise the cybersecurity industry between 2022 and 2023 - and it did not succeed. The reasons are complex: AISA withdrew, funding may have lapsed, and other factors might have played a role.

But if we are now being asked to try again, it’s reasonable to ask: what has been learned? What has changed? Saying “the government wants it” is not an answer - it’s a way of avoiding the contradictions that professionalisation continues to raise.

I understand that some may say the story is more complex - and no doubt, it is. But complexity doesn’t dissolve responsibility. It sharpens the question: Who, then, is accountable when professionalisation fails?

Sources:

- AusTender, 12 Jul 2021, Provision of Cyber Security Workforce and Skills Forecasting

- AustCyber, 20 Mar 2023, Australian cyber security leaders join forces to build sustainable career pathways for industry professionals

- AustCyber, 15 May 2023, ACSP LinkedIn Announcement

- AustCyber, 15 May 2023, Australian Cyber Security Professionalisation program: Meet the co-design team

- AISA, An Update on the ACSP Program

- AustCyber, Nov 2023, Australian Cyber Security Professionalisation program

- Brandon How, InnovationAus, 9 Oct 2024, AustCyber reborn as Australian Cyber Network

- Benjamin Mosse, Damien Manuel, Mike Trovato, 5 May 2025, Listening Before Leaping: AISA’s Cautionary Path on Professionalisation

- ABN Lookup, AUSTRALIAN CYBER SECURITY GROWTH NETWORK LIMITED

- Australian Government, Growing and Professionalising the Cyber Security Industry Program

- Jason Murrell, Tony Vizza, and Tom Finnigan, 19 Mar 2025 The Fight to Professionalise Cyber Security

- Benjamin Mosse, 26 Mar 2025, The Spectres of Cybersecurity Professionalisation