When a Cybersecurity Standard Becomes the Villain

17 May 2025Nothing says “we’re here to help small businesses” quite like charging $95 to read the rules - and threatening to sue if you share them. This is the story of how one closed standard gave birth to an open-source revolt that refuses to play by its rules.

Everything my three-year-old son wants to do is illegal. He wants to smash, climb, take, throw, defy. He wants to break every house rule, violate every norm, and commit every domestic crime imaginable. From a psychoanalytic standpoint, it makes perfect sense. The very things he’s told not to do become the “object a” of his desire - the forbidden door through which he discovers the intoxicating taste of inner freedom.

The origin story of OpenCASE isn’t far removed from that same structure of rebellion.

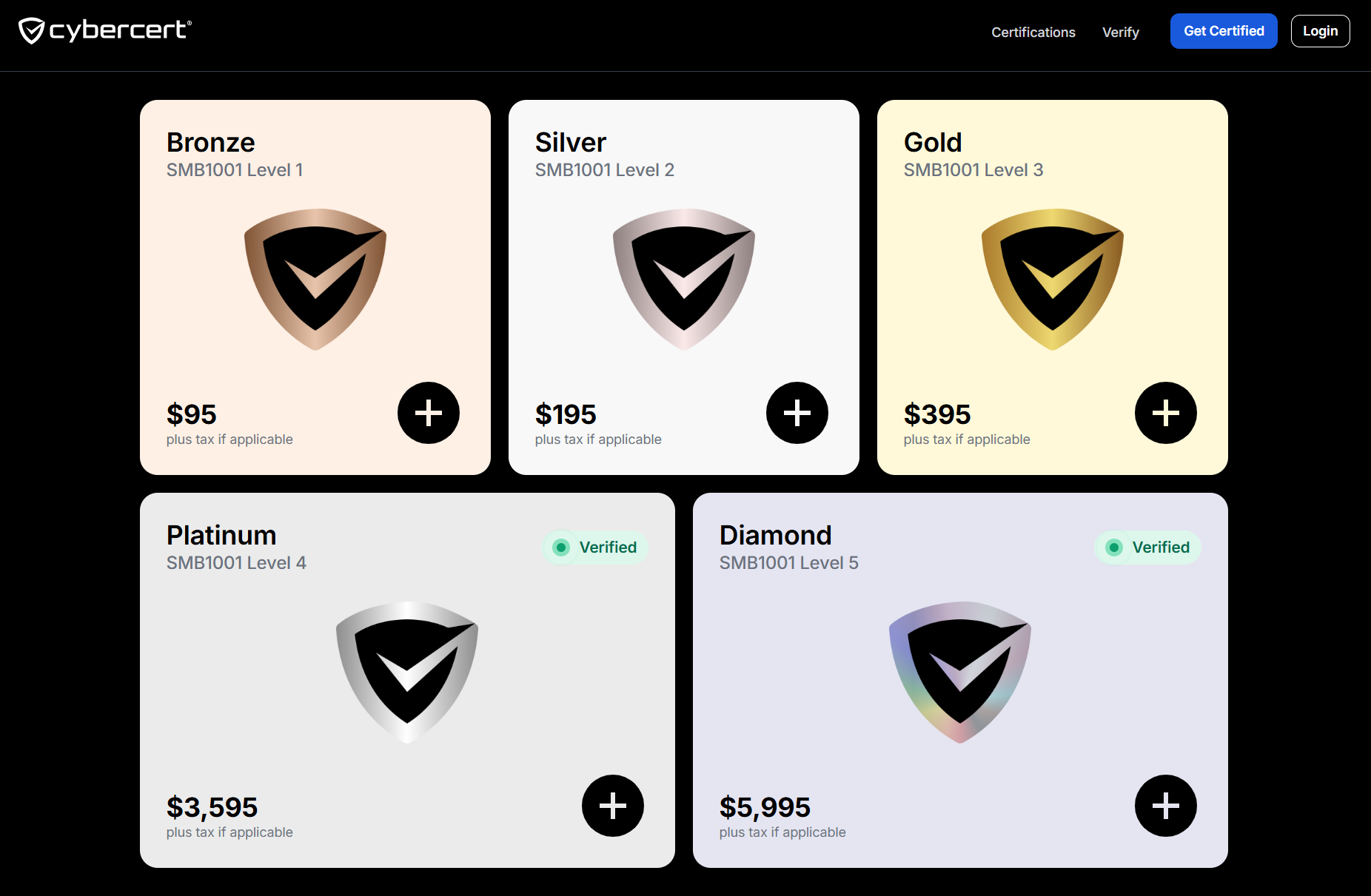

It begins with a critique of SMB1001, a cybersecurity standard aimed at helping small businesses. On paper, a noble goal. But there’s a catch: in order to even view the standard, one must pay between $95 and $995 USD. Worse, the licensing agreement is draconian. Sharing the document - even in good faith - could expose you to claims of irreparable harm or even injunctive relief. The standard is updated annually, so the meter keeps running.

Behind this paywall is DYNAMIC STANDARDS INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD (DSI) - an Australian for-profit company (ABN 47 650 892 514), established in 2022. Its Steering Committee includes a mix of public and private sector entities, to ensure the standard stays “fit-for-purpose.”

Curiously, even Ashley Bell, the Assistant Secretary from Home Affairs leading Australia’s push for cybersecurity professionalisation, holds a seat at this table (in front of Jason Murrell).

Furthermore, beyond the fees required to download the PDF standard, companies seeking accreditation badges must pay a separate entity called CYBERCERT PTY LTD (ABN 87 662 681 423). According to ASIC, this entity has the same shareholders as DSI.

For the pseudonymous critic “Corch,” this closed, monetised standard represented a contradiction too glaring to ignore. It was precisely the kind of Symbolic Order - policed, priced, closed group and layered entities - that demanded rupture. Thus, OpenCASE was born: an open-source, free, collaborative standard that anyone can contribute to, fork, and build upon.

Where SMB1001 asserts control, OpenCASE invites freedom. Where one extracts revenue, the other distributes freely. One builds credibility through a closed committee. The other through open collaboration.

OpenCASE is an Act born from the belief that SMB1001 betrayed its own ideals - an eruption where fidelity to the cause could only be expressed through defiance. It is through this feeling of betrayal that Corch discovered an inner freedom and desire to Act.

And like any true Act - one that severs rather than supplements - it is born through violence. Here, the analogy to Alien (1979) becomes inescapable. In that film, the Alien gestates inside its human host, feeding off it until the moment it tears through the chest cavity in a grotesque birth. The creature does not negotiate, empathize, or apologize. It simply is - stronger, colder, and immune to legacy authority.

OpenCASE is the Alien that burst forth from SMB1001 - unexpected, uninvited, and entirely of the system’s own making. Peter Maynard and Jason Murrell now hold the rare distinction of fathering two cybersecurity standards: one by design and ambition, the other by accident - when they became the unwitting hosts to contradictions too large to contain. Both standards are now inseparable. OpenCASE historically exists because of SMB1001.

In the movie, the Alien first appears small, vulnerable, even pitiful. The crew underestimates it. They arm themselves with plans and tools, convinced it can be managed. But as we know, the creature grows stronger by the hour - and begins picking them off, one by one.

Here’s the twist: the company funding the mission knew about the Alien. Not only did they know - they wanted it retrieved. The creature, they decided, was worth the human cost.

SMB1001 is backed by a group with clear profit motives. It needs to be sold, protected, licensed. OpenCASE, in contrast, cannot be commercialised. Like the Alien, it exists outside the logic of the marketplace. It is a threat precisely because it refuses to be sold or play by any capitalist rules.

In the movie, the crew finally understands: the Alien cannot be stopped through negotiation, policy or procedure. Therefore, they try to self-destruct the ship. Only through desperate courage and quick thinking does Ripley kill the Alien so that the movie might have a happy ending.

The tension between SMB1001 and OpenCASE is only just beginning. But it’s more than a conflict over standards - it’s a confrontation between two intertwined worldviews. Between those who sell protection, and those who build it freely. Between control and freedom. The latter responding to the former.

The key question is not whether OpenCASE is better than SMB1001, but whether small business owners, security professionals, and policymakers, will have the spine to back a system not built to exploit them. If we continue to pay to obey, we deserve the accreditation bodies that devours us. But if we choose to build together, in the open, then perhaps the Alien isn’t the monster.

Perhaps the real monstrosity is a system that dresses up profit as public service - and those who, while fully aware of this, continue to participate in it under the convenient shelter of disavowal: “I know very well what this is, but still… [insert explanation]”